Ironton Register, Thursday, January 23, 1896

Author Unknown

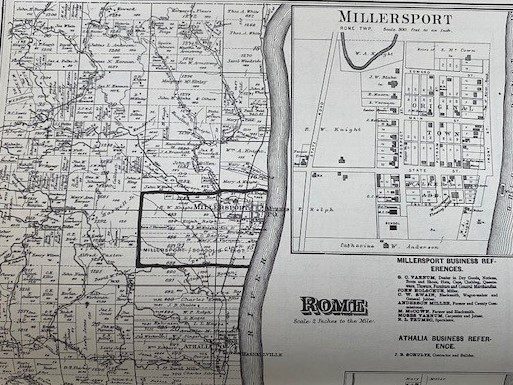

Reminiscences of a Millersport Man – I first saw the light of day at Millersport (Millers P. O.) in Rome township, April 4, 1844. I have a clear recollection of events since the cholera season of 1853. Many died that Summer, including Fannie McKnight, mother of W. F., C. B., and J. T. McKnight. Wm. Gibbs ran a wool carding machine, the same one that was afterward taken to or near Burlington and operated by Elijah Rolph, W. F. McKnight, Andrew Griffith, Andrew Miller, and others.

The first real work the writer ever did was at this machine at seventy-five cents a week. Mr. Rolph had two heavy oxen instead of horses for the motive power, and one could stop the machine at pleasure. I was to watch him during his “turn at the wheel” and keep him going. A change was made every hour and sometimes often in very warm weather.

While the other ox that had not learned the art of stopping the machine was taking his turn, my duty was to help in the carding room. I finally learned the trade so well that I could “run the machine” alone, and at the age of fifteen, I operated it alone for Andrew and Warren Miller and gave the patrons satisfaction. [I remember that] wool was brought from nearly all over Lawrence and Gallia Counties, Ohio, and Cabell County, W. Va. In those days, the whole community wore homemade jeans. The women and girls wore linsey. This machine made the wool into rolls, which the women spun into yarn.

My earliest recollections are of John W. Dillon, now a prominent minister of the M. E. church and well-known to the Ironton people. He is a strictly self-made and self-educated man. When he was a young man, not yet grown, he used to haul “cordwood” from the hills to the river. When I was too small to go with him to the woods, I would wait for him at the foot of the river hill and drive in the level lane to the river.

While I did this, he would take his Testament from his pocket and study the scriptures. He put in all his spare time to study. Before this, he had been converted into one of the old-time revivals. He was a tall, slim, awkward-looking fellow, and when he first began to exhort, people used to say he did not know what to do with his hands while talking. I used to almost worship that man, and I shall never forget his struggles, trials, and the difficulties he had to surmount to get where he is now. It is an object lesson of what courage and perseverance will accomplish.

Of preachers in the days from 1852 to 1857, I remember Bradrick. He was a great revivalist. In mid-winter, he would pull off his coat and vest and preach and sweat like a harvest hand. In those days, they preached great power. I used to think there was a literal hell, and I believed implicitly that men would swim around in a liquid fire like molten iron or cinder. I got this idea from the oft-repeated phrase “lake of fire and brimstone.”

The “quarterly meetings” in those days were important events, and I can remember how my father and the other members used to get out their “cloth coats” and “stocks.” A stock was a made necktie about as wide and stiff as the leather stocks they used to put on recruits at the beginning of the late war to cause them to hold their heads erect. The elder came with much dignity and solemness.

The hymns were “lined” then, two lines at a time, and sung by all in the house. It was a sober, solemn time, and woe to the person who did not kneel when the minister said, “let us all kneel and pray.” It meant that all must kneel whether they prayed or not. The quarterly love feast was announced for a certain hour and was held with closed doors, and at the hour named for the service to begin, the doors were closed and bolted.

No outsiders could remain at these meetings without publicly declaring a determination to lead a better life. The leader passed around and personally examined each one and reproved, admonished, or praised each one according to the experience given.

The schoolhouse was made of logs, and we had three months of school in winter. The first teacher I remember was named Harris. He kept hickory withe in his hand all the time during school hours. We did not call them teachers. We called them masters, and they were more masters than teachers. They did not teach us _________.

We recited lessons in ______ ______, got the poetry out of the reader by heart, and spoke it in a sing-song tone without any reference to punctuation. He did plenty of whipping, and the directors considered this set the best qualification. Another teacher was named Green. In those days, we wrote with quill pens, and the masters made the pens. We hunted the goose quills and carried them to the masters.

Later, D. G. Dawson, S. McCown, and W. F. McKnight taught. Dawson was very eccentric and smoked his large pipe during school hours when he wanted to. He was a pettifogger. During a trial one day before a Justice of the Peace, there were several lady witnesses on the opposite side to him who had answered him rather curtly on cross-examination. During a brief recess, he drew his large pipe and began filling it with “long green.”

The ladies looked on when he turned to them and said, “Ladies, is tobacco smoke offensive?” “Yes sir,” one of them answered, “very much so.” “Then you had better leave the room, for I am going to smoke,” said Mr. Dawson. S. McCown was a teacher and a master and taught a good school. He was elected Probate Judge and died in office, succeeded by C. B. Egerton.

John Clark, the father of D. H. Clark, kept a large store. He was a local preacher, and I remember him as a truly good, kind, and sympathetic man. One day a neighbor’s house burned down with all he had in it. A day or two afterward, neighbors gathered in Mr. Clark’s store, discussing the loss and stating how sorry they were. Finally, Mr. Clark said, “I am sorry, five dollars. Now how much are the rest of you, sorry?” I remember that quite a sum was raised for the unfortunate man.

I used to like to watch the “line” boats go by. They had clippers in those days and raced like mad. The two opposition lines were very hostile toward each other. I remember the names of several that ran between Cincinnati and Pittsburg, viz Buckeye State, Bay State, Thomas Swan, David White, Messenger, Crystal Palace, and Keystone State.

Once when my father had been on a trip to Illinois, he came home on one of the new liners. Some poets had composed about twenty verses for the new line of boats, ridiculing the old line. I set these to a song and could sing every verse of it. I now remember but two verses to wit:

The Buckeye’s time is very good

Although she burns tar, coal, and wood,

But faster will she have to kite

To catch the Swan or David White.

The Messenger, although a tub,

She lives upon the best of grub,

We don’t see how she makes it pay,

She is so long upon the way.

The Doctors cut a figure in society before the war. Dr. C. B. Hall had a large practice. Dr. I. T. Monahan came down from one of the northern counties. He was a hustler. He would jump on his horse and start a gallop over the country for half a day like twenty people were half dead when no one had called for or sent for him.

A bitter rivalry sprang up between Dr. Hall and Dr. Monohan, and many predicted they would kill each other. This was about 1856-8. One morning, several copies of poetry reflecting on Dr. Monahan were found pasted up on the store and shop doors. It was written with a pen on foolscap paper. I was always a great singer when I was a boy, and like the steamboat poetry, I set it to the song and could and did sing it, and in retaliation, the doctor shot my dog.

0 Comments