BIG SANDY VALLEY – PERSONAL OBSERVATIONS OF PILGRIM

Ironton Register, Thursday, July 14, 1892

Very few of the Register’s readers do not know that the Big Sandy River empties into the Ohio River about ten miles above Ironton. Yet, few of them have ever thought that the shallow sickly looking stream, nearly choked with sand, is the main thoroughfare to and from the world for thousands of human beings.

It is 120 miles from Catlettsburg to Pikeville, Kentucky, the head of navigation by stream on Louisa Fork, and fully one hundred miles to the head of navigation on Tug fork, so that the two rivers open up a very large scope of rich mineral land. A very small part of this vast boundary is within reach of railroads.

Nearly forty miles of Ohio and Big Sandy Valley Road and nearly two miles of the C. C. & Chicago terminate at White House mines. Passengers are not allowed to travel on the last mentioned road, and the trains go over it once a week to take in supplies and carry away the coal mined at the White House.

Our friend Lu. Johnson of Howard, and later of Ironton, is the “King” at these mines, and he is a credit to us all in a business way. Straight and reliable, he has both the operators’ confidence and the workmen’s respect and love.

A young man like that speaks well for the thorough training of the old-time furnaces, where a man is expected to know everything and, like the ideal charcoal manager, W. H. McGugin, Esq., always ready to tell a pointed story, over which you can laugh and reflect for three weeks. Good, honest, square fellows that make a pilgrim forget his worries and whose hearty handshakes annihilate the blues.

The U. S. government is now putting up a system of locks and dams on this river, and our young friend B. F. Thomas is the engineer. He is also a grand young man and very popular in Louisa, where he lives. He said that the appropriations soon to be made would complete the first dam and give a start to other improvements farther upstream.

The highways are in desperate condition; some of their bridges are down, and others are far more dangerous than if they were down. There is no good bridge over any creek or branch one hundred miles above Louisa, Kentucky. Nearly every traveler requests the driver to wait till they walk across.

Horseback travel is by far the most satisfactory, but good horses are very scarce, and others are so nearly worn out that a man is only half-mounted when he undertakes a journey on one of them. The people are very kind and hospitable, are lasting friends to any well-meaning traveler, and will never fail to pay back an enemy in his coin if the chance occurs.

The rafting of timber, as well as the chopping and hauling, engage the time of most of the men, and so much of the farm work is done by the women who appear to enjoy the outdoor exercise. This kind of life brings about the fact that some of the best-looking specimens of the female sex live on the waters of Big Sandy.

It is not generally known that the first fight in which the 2nd WV Cavalry was engaged took place at Jennie’s creek about three miles back of Paintsville, in January of 62, when Amos McKee of Co. B. was killed and also Albert F. Leonard, an Ironton schoolboy, a member Co. F., fell dead at the same fire.

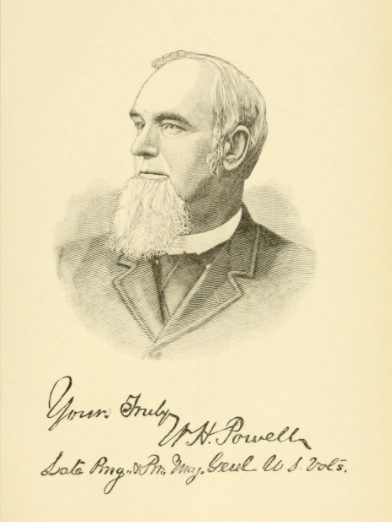

Jennie’s creek is a small stream running into Paint creek about three miles above the town, but so peculiar a stream that it nearly surrounds the town before it passes to its destination. A part of its valley is called “Hell gate,” and it was there that Gen. Humphrey Marshall had fortified and where Gen. W. H. Powell led his men to attack him.

With only horse pistols used in the Mexican war, it was necessary then for our force to catch a man before they could kill him. Most of the enemy got away, but it is a wonder that more of our forces had not been slaughtered on that occasion.

Vandevort and Bertram of Haverhill were wounded at that time. Marshall’s entrenchments remain to this day, and some of the old residents tell of that dreadful day long ago when the clanging sabers of the Yankees sent the Johnnies “whirling up” the Big Sandy Valley.

Nearly every creek is an avenue for logs on their way to Ironton. Every road once led to Rome, but now it takes every stream to furnish food for the ravenous saws that whirl and glide on the river bank at Ironton.

The triangle of the Yellow Poplar Co. is on the ends of some of the most magnificent poplar logs ever cut, now laying high and dry, waiting for a tide to bring them where the saw can shape their destiny to become pleasant homes for men.

Photo from The Lawrence Register Archives

Our Mr. Clarke may not be a man of much kindred, but his “ties” are everywhere. A very large raw-boned man was “hewing to the line” away up one stream when I passed by on my “critter,” and when I asked him whose ties those were, he said “Clark’s” and pounded away.

It is a comfort to know that the C. & O. now has control of the Big Sandy Valley railroads. We shall soon see them reaching out for Southern connections and giving us one more route to the sea at the peerless harbor of Charleston, S. C. The immense coal deposits of the Big Sandy Valley will make it a hive of industry in a few years. Its exceedingly low grades in crossing the mountains will make its railroads the most popular routes to the seaboard, and its waterways will add to its value as a coal center till it becomes part of the land of the free.

0 Comments