The advent of the Quakers into Ohio

First members of that religion settled on the present site of the village of

Proctorville, Ohio, then spread out in many directions.

By R.C. Hall, Ph.D.

Herald-Advertiser, Huntington, WV 17 July 1938

Typed by Lesli Christian

As readers of these columns know, we have referred quite often in the past to the early settlement of Friends, commonly known as “Quakers,” on the site now occupied by the village of Proctorville, Ohio. According to the most reliable data we could secure, we found that one Jesse Baldwin had settled. In 1797, in what is now the western end of Proctorville, on or near the site of the James I. Easton Sr. home.

We have often wondered, and probably others have wondered, just who this Jesse Baldwin was, what became of him, who was associated with him in the settlement of this place, whether or not he was the first actual white settler in the neighborhood and just what relationship the settlement of Quaker Bottom bore to the other early Quaker settlements in the old Northwest Territory of the United States of America. Now, it appears that many of these facts have recently come to light. And as they have come to us from a very authoritative source, we are very glad to pass them on to others who may be interested in them.

It appears that some of our writings came to the attention of Harry Dixon of Londonderry, Ohio. Mr. Dixon had, he stated, recently come into possession of some data on the early Quakers of what is now Ohio – data that has just come to light, so to speak, within the past couple of years or so.

He kindly offered to put this in our hands for a time for our study, and use, if we saw fit, in a further narrative of the story of Quaker Bottom and the Quakers in general. To say that we are delighted over this opportunity would be stating it mildly. And we hope those readers interested in the subject will derive some pleasure and profit from the facts we hope to make available to them in this sketch.

Source of Facts

First, let us explain the source of some of these facts. The more important ones are contained in a letter written by Gershom Fardew at the request of William Foster of England, who was seeking information regarding the first Quaker settlements in America.

It appears that that letter was written in 1863, was copied by J.R. Ellis in 1896, then copied from the Ellis copy by Maggie M. Huff in 1908, and finally, a copy was made from the Huff copy in 1937 by Bertha Janney Holland. It is this letter that Mr. Dixon, with other data substantiating it, has placed in our hands. It is entitled “First Friends in the Northwest Territory” and, as such, an article may be described as a brief history of the establishment of the Quaker church in Ohio.

But before tracing the development of Quakerism in the northwest, we would like to say that the data in question corroborates what we already had in regard to the settlement of Jesse Baldwin at Quaker Bottom in 1797. But it goes much further than this. It shows that the name Quaker Bottom, which has clung to the Proctorville region for over a century and a quarter, is fully justified as it was actually the site of the first Quaker settlement northwest of the Ohio River.

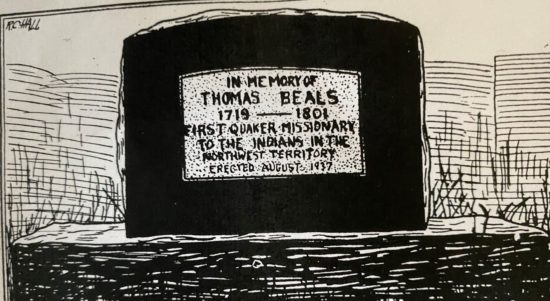

Moreover, it shows that the Quaker missionary, Thomas Beals, had visited this vicinity even earlier as a missionary to the Indians. In fact, the whole history of Quaker Bottom, as well as of Quakerism in general in the Northwest, appears to begin with Thomas Beals. So we ought, perhaps, to begin our consideration of the subject with a brief sketch of his career.

Thomas Beals

Thomas Beals was born on March 3, 1719, in Chester County, Penn. He was a son of John and Sarah Beals, The latter, whose maiden name was Sarah Bowater, came from a family of Friends in England. Thus the Ohio Quakers descended from England by way of Pennsylvania, so to speak, which agrees with the historical and traditional reports of Pennsylvania as the original Quaker stronghold in America.

Thomas Beals married Sarah Antrim and moved to North Carolina in 1748 when he was 29 years of age. After visiting for a time at Gane Creek, he and his family, accompanied by two other young men, moved to the site of New Garden in what later became Gilford County, N.C.

It is claimed that no other white person lived there at that time and that their sufferings in the wilderness were great. However, their situation was perhaps somewhat better in a short time for Thomas Beals’ brothers, John and Bowater, together with Richard Williams, Thomas Hunt, and Robert Sumner, came and settled in the same vicinity.

Apparently, Thomas Beals was about 34 years old when he became a Quaker preacher. That was in the year 1753. There appears to be no record of how long he remained with the Quaker colony, which had then been established at New Garden.

However, there is an account of his removal to Westfield, Surrey Co., N.C., where he is said to have “raised a large meeting,” or, as some would say, he established a large church. It is supposed that he must have dwelt for some 30 years in North Carolina, during which period he began and continued his practice of making lengthy visits to various tribes of Indiana.

“On the 28th of 8 months 1801, Thomas Beals died and was buried on the 31 of the same month near Richmond, Ross County, Ohio, in a coffin of regular shape, hollowed out of a solid white walnut tree by his ever-faithful friend Jesse Baldwin, assisted by Enoch Cox and others and covered by a part of the same tree, which was selected for the purpose by the deceased while living. The coffin was not hollowed by burning, as stated by Mary Howett of England in her book to her cousin in Ohio.”

Missionary Journey

In the year 1775, Thomas Beals, with a nephew Bowater Sumner, William Hiatt, and David Ballard, started on a missionary journey northward, apparently intent on visiting the Shawnees north of the Ohio River. Now, it should be noted that they set out just at the beginning of trouble between England and her American colonies. In fact, their journey almost coincided with the outbreak of hostilities, which proved to be the beginning of the Revolutionary War.

Naturally, it was a period of great excitement throughout the colonies. Suspicions were rife; hatreds deep-seated; fear prevalent, and trouble easily found. Citizens along the frontier had extra worries. In addition to the natural hardships of pioneer life, they were in constant danger of Indian raids. Now that war was apparently about to break out with England. The frontier was very nervous over alliances between the British and the Indian tribes.

Therefore, frontiersmen were likely to look askance upon any person dealing in any way with the Indians. And so when Mr. Beals and his party happened to pass by a frontier fort in the neighborhood of Clinch Mountain, Va., they were promptly arrested as spies.

Accordingly, they were taken back to the fort for trial on the charge of having treasonable contact with hostile natives. But the officer, hearing that one of their captives was a preacher, decided to postpone the trial until he could hear a sermon. Thomas Beals apparently decided that this was not only a chance to prove to his captors the true mission of the little band of Quakers but also to have an influence for good upon the soldiers.

At any rate, he accomplished both objectives apparently, for him and his friends were set free and permitted to continue their journey, and one of the young men in the fort professed conversion and later became a member of the Society of Friends and remained faithful through the rest of his life.

Cross Into Ohio

After this experience with the people of the fort, Thomas Beals and his companions proceeded on to the Ohio River, which they crossed into what is now the state of Ohio. They journeyed on, probably as far as what is now eastern Indiana, stopping here and there to hold meetings with the Indians, whose response to their preaching appears to have been quite satisfactory.

At any rate, they returned to their homes filled with enthusiasm, and Thomas Beals said “that he saw with his spiritual eye seeds of Friends scattered all over that good land,” and he expressed the belief that someday there would be more Friends in the region northwest of the Ohio River than in any other region on earth. He also appeared to have the firm conviction that he would live to see many of the Friends settled in that region.

Of course, it appears that the prime consideration of Beals was the spiritual condition of the Indians, and in 1777, accompanied by one William Robinson and an interpreter named Isaac Ottoman, he again set out to visit some of the tribes of the Northwest.

But again, his object was frustrated by frontier suspicion, apparently. For upon arriving at a small meeting of Friends in western Pennsylvania, Beals, and his companions were taken and forced to a place near Fort Pitt where, after some delay, they were sent back home. But Beals was not to be discouraged. He made a third attempt. And this time, he met with even sterner opposition.

Journey Interrupted

Not only was his journey interrupted, but he was kept under guard for a time and imprisoned in an open barn, where he must have suffered much from the cold. Finally, the coroner, who had had charge of him, released him from confinement and permitted him to hold services for the soldiers, but would not permit him to continue his journey, so once more, he returned to his home.

However, in 1781, Thomas Beals moved from Westfield to Blue Stone in Giles County, Virginia. Here he and his family and associates suffered greatly from a lack of comforts and almost of actual necessities of life. Their situation was made worse, too, by the hostilities of the Indians.

Although the Quakers had an almost uncanny knack for getting along with the natives, the latter, probably urged on by the British, did not, in this instance, spare the little band of Friends at Blue Stone. In fact, James Horton, a son-in-law of Beals, was carried away by the Indians into captivity. The Perdew manuscript states that “from the most reliable information that could be obtained,” Horton was taken to “old Chillicothe near Frankfort, Ohio, and there was put to death.”

If this information were accurate, James Horton might rightfully be considered a “Quaker Martyr,” and the first such martyr in what is now Ohio, the site of his martyrdom being the Chillicothe village near the site of the present city of that name and one of the several Indian villages called Chillicothe.

Asked To Return

The Perdew manuscript also states that “Nathan Hunt says they sent a committee to move him back to Westfield, N.C.,” which evidently means that the Quakers did not approve of Beals’ move to Blue Stone and sent a delegation to inform him that fact and to persuade him to abandon his new location. Anyway, that was done, although the settlement had attained the size of 20 to 30 families.

But Beals, like Banquo’s ghost, would not go down. His indomitable spirit appears to have next led him to Lost Creek, Tennessee, in 1785 and to Grayson County, Virginia, in 1793. Again reliance must be placed on Perdew, who evidently relies implicitly upon Hunt, for he states that at these places, “Nathan Hunt states that Thomas Beals set up meetings and says that he was very jealous for the support of the Testimonies of the Society of Friends.”

It appears that during his first visit to the region north of the Ohio River, Thomas Beals visited the bottomlands opposite the mouth of the Guyandotte River and upon which the Friends were destined to leave the name by which they are commonly known. If this is so, Thomas Beals was undoubtedly the first Quaker in Quaker Bottom and must have visited it as early as 1775.

While there is apparently no proof of this supposition, there is strong evidence of it, as we shall cite a little further in this sketch. Anyway, no settlement was made in Quaker Bottom at that time, and when it was made, the distinction of making it went to others. Thus the Perdew manuscript states: “In the 8 months 1796, Jesse Baldwin and family, members of the Society of Friends from Westfield, North Carolina, and Phineas Hunt, and his family, all members of the Society except himself at that time, but soon became a member; moved to the Virginia shore.”

Crossed the River

This evidently means that they moved to the shore of the Ohio River on Virginia, now West Virginia, side. Evidently, they settled in what is now Greene Bottom, W.Va., and remained there for about six months, for the Perdew manuscript states: “In the 2nd month 1797 Jesse Baldwin and Phineas Hunt cross the Ohio River with their families and settle opposite to Green Bottom, near to each other.”

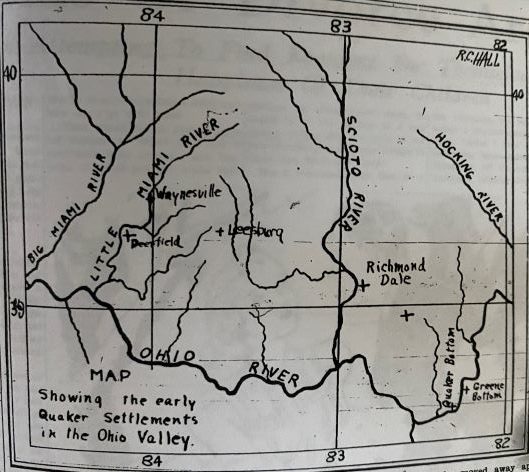

Meanwhile, however, in 1795, John Harlan and his wife Marguery, sons Aaron, Samuel, and Moses, who were members of the Society of Friends, came from Kentucky to the Miami Valley and settled at Deerfield, about four miles below the present town of Morrow.

The Northwest Territory was apparently proving quite attractive to the Quakers, for we find that “On the 8th day 5 mo. 1797, John Winder, his wife Margaret, and their children, Abner, Mercy, Elizabeth, and James, the latter’s wife Deborah, sons-in-law Isaac Warner and family, and Levi Warner settled at what was known as High Bank on the Scioto River. Isaac Warner’s family consisted of himself, his wife, and three daughters, Lydia and William Chandler, and his wife Hanna was also of this group, which apparently came from Westland, Pennsylvania.

This settlement of High Bank was on the east side of the Ohio River near the end of the railroad bridge, which was later built there, and thus about four miles downstream from the present city of Chillicothe. Thus, we see that at least three Quaker settlements had been made in the Northwest Territory and in what is now Ohio before the opening of the Nineteenth century.

Baldwin Moved Again

The one opposite Greenbottom, however, was destined to be merely a temporary one. The Perdew manuscript relates its removal thus:

“In the latter part of the year 1797, Jesse Baldwin, after raising some corn and vegetables opposite Greene Bottom, moved some 18 miles down Ohio and settled in what is called Quaker Bottom in Lawrence County, Ohio, opposite the mouth of the Guyandotte River and the present town of that name.

“Here he was very soon joined by Nathaniel Pope from Grayson County, Va., whose wife Martha was a member and himself sometime after.

“I note this place of more than usual interest, it being the spot where Friends in the Northwest Territory first set down to hold a meeting for Divine worship, which will be noted at proper date.”

The writer of the manuscript evidently wished to discuss some other matters which transpired between the date of the first Quaker migration and the holding of the first meeting in Quaker Bottom. When he returns to the latter subject, he continues:

“In 1799, Thomas Beals, who had visited this country 24 years before, now moved to Quaker Bottom with his family and sons, John and Daniel and their families, and grandson Abel Thornburg, whom they raised, his parents being dead, and Obadiah Overman and Abigail his wife and family, all from Grayson County, Va.

“On their arrival, they opened a meeting for worship in the dwelling of Jesse Baldwin, which was regularly held during their residence at that place, which they unitedly believed was favored with the Master’s presence. The nearest meeting to them was Westland, Penn.”

Place Well Named

Thus we see that Quaker Bottom was well named and is really entitled to this name, which has clung to it now for over a century and a quarter after the departure from it of its last Quaker settler. For it was not only one of the first Quaker settlements in the Northwest Territory and in what is now Ohio.

But it was here that the first Quaker meeting was held, and the first Quaker church was organized northwest of the Ohio River. Just what was so attractive about this site for these early settlers is not indicated in the Perdew Manuscript.

Of course, for us who were born and raised in Quaker Bottom, many of the virtues of the place are self-apparent. We can, without effort, name dozens of qualities that, we think, distinguish Quaker Bottom as the finest community on earth. We admit, of course, that we may be slightly prejudiced in its favor.

Yet we insist that these early Quakers knew a fine location when they saw it, although, as we have suggested, they apparently left no reason for their choice. Probably it was made on the basis of a report made by Mr. Beals after his first visit to the Northwest Territories or possibly after settling opposite Greenbottom. Mr. Baldwin may have explored the region and discovered this long, wide bottom with its luxuriant growth of virgin timber, indicating the fertility of the soil, and decided that here would be an ideal place for the people of his faith to settle and to grow into a large community.

Indians Had Gone

Then, too, most of the hostile Indians had already left this region, and white settlers had not yet begun to take up the land. Then, too, it was probably thought that Quaker Bottom was beyond the limit of the Ohio Company’s land and, indeed was the western end of it, where the nucleus of the Quaker settlement was established on the site of the present village of Proctorville. However, some of them apparently were not aware of the exact location of the line and settled within the limits of the Ohio Company’s purchase.

Anyway, there was certainly nothing to indicate that these early Quaker settlers would soon be disturbed in their new location. The primeval forest stretched to the north, east, and west, unbroken for hundreds of miles, except by a few frontier settlements, such as Marietta and Gallipolis, the latter being their closest neighbor so far as a white settlement was concerned. Before their doors flowed, beautiful Ohio showed no signs to them that someday it would arise in its might to flood the homes of the people who would later choose this site for a town.

Of course, those Quakers who did settle in the Ohio Company’s purchase could not obtain legal title to any land there except by purchase from that company or from others who had already purchased there. Nor could those who settled on the site of the present village of Proctorville have obtained land there except by purchase from the government under regulations governing the sale of congress lands, of which this region was a part.

Apparently, the Quakers, or some of them, thought they could hold land here by pre-emption, or “squatter’s right” and did not understand the law providing for the sale of land in the Northwest Territory. No doubt, however, most of them were more interested in their religious affairs than they were in securing lands.

Quaker Headquarters

Having found a large, fertile, and unoccupied valley far from the ordinary course of civilization, where they could worship the Lord according to the dictates of their own consciences, these peace-loving people appear to have been content to let other matters take their own course.

However, according to the words of praise for the place contained in the Perdew manuscript and the stress it places upon the importance of the settlement here, Beals, Baldwin, and their associates must have intended to make Quaker Bottom a permanent community of Friends.

And although they did not succeed in that ambition, it is interesting to note that during the short period of its existence, the settlement of Friends at Quaker Bottom was the Quaker headquarters, so to speak, of that section in the Northwest Territory and in what is now the state of Ohio.

Here the first Quaker church was organized, and here laid the foundation for a Quaker settlement which, under other circumstances, might have become a permanent settlement of Quakers. As to their removal, the Perdew manuscript says:

“In the spring of this year, 1801, Thomas Beals, Jesse Baldwin, John Beals, and Daniel Beals moved from Quaker Bottom, and they, with Enoch Cox and their families, settled up Salt Creek, near the present town of Adelphia. At this place at Taylor Webster’s Highbank, and at Hugh Moffett’s, meetings were held by Friends of several settlements coming together at such place as circumstances most favored.”

There is no hint here, apparently, as to the reason the Quakers abandoned their homes in Quaker Bottom. In fact, the record does not state that all did so at the same time. On the contrary, we have evidence that they did not. At any rate, the account has been handed down of at least one Quaker here as late as 1812.

The Last Squatter

He was living in what is now the Null farm or near the north boundary of that farm by the large spring near the foot of the hill. This was on land purchased by this writer’s great-grandfather and was a part of the Ohio Company’s purchase. When he learned that the land could not be held by “squatter’s rights,” he moved away, apparently without objection or regret.

The name of this squatter has not been preserved, so far as we have been able to learn, but apparently, he was related to, or associated with, some of those Quakers whom we have been discussing and who formed the original white settlement on the side of Proctorville.

Although the original settlement of Quaker Bottom by the Friends lasted about four years, if it ceased to exist in 1801, it became a landmark in the history of that denomination. And apparently, it did cease to exist in that year, for even if a few adherents to that faith did remain in the neighborhood some years longer, the leaders of the movement, according to the Perdew manuscript, had gone and nothing remained to distinguish it as a Quaker settlement.

It became a landmark, however, as what may be called the point of entry of Quakerism into the history of the Northwest Territory. Thereafter, Friends became very active in this region, and their meetings became more and more numerous.

The very same spring in which Thomas Beals, Jesse Baldwin, and others moved from Quaker Bottom to Salt Creek, a number of families of Friends, having settled near Waynesville, united to hold a religious service. These families consisted of 24 parents and 57 children.

Among those attending this religious meeting, the names of the following have been preserved: Roland Richard, Lydia Richards, Abijah O’Neal, Ezekiel Cleaver, Abigail Cleaver, David Halloway, David Faulkner, Judith Faulkner, Daniel Pugh, James Mills, Lydia Mills, Samuel Kelly, Hannah Kelly, William Walker, David Painter, Martha Painter, Levi Lukens, and Anna Lukens.

Death of Beals

But to return to the pioneer, Thomas Beals, who was the leader of the movement of Friends into the Northwest Territory. Of the conclusion of his earthy pilgrimage, the Perdew manuscript says:

“On the 28th of 8 mo., 1801, Thomas Beals died and was buried on the 31 of the same mo., near Richmond, Ross County, Ohio, in a coffin of regular shape, hollowed out of a solid white walnut tree by his ever-faithful friend Jesse Baldwin, assisted by Enoch Cox and others and covered by a part of the same tree, which was selected for the purpose by the deceased while living. The coffin was not hollowed by burning, as stated by Mary Howett of England in her book to her cousin in Ohio.”

It appears that William Puckett, Hugh Moffet, and others were interred in the same plot of ground, about which the Friends of Indiana caused a stone wall to be erected shortly before the time of the preparation of the Perdew manuscript. In fact, although Mr. Perdew appears to have taken no credit for it, the preservation and marking of that plot, so important in the history of the Quakers and of Ross County, was chiefly due to the energy and enthusiasm of Mr. Perdew himself.

For the Friends had long ago left that vicinity and had it not been for the protective wall, the site of the last resting place of the pioneer Quaker missionary to the Northwest Territory would probably have been entirely unknown.

As it was, the place became neglected and fell into decay until just recently. Meanwhile, the little village of Londonderry, or Gillespieville Post Office, as it is officially known, and Leesburg, had become centers of Quaker activities. Finally, under the auspices of the churches of Friends of these two places, a movement was started for the preservation and more suitable marking of the site.

A granite company was commissioned to erect at the grave of Thomas Beals a monument of granite, three feet long, two feet in height, and eight inches in thickness. This site is on the Jacob Caldwell farm, New Richmond Dale, Ross County, Ohio. The new monument was dedicated to appropriate ceremonies, in which the Ohio Archaeological and Historical Society participated.

Held Yearly Meeting

In the autumn of 1802, the widow of Thomas Beals, her son John and Daniel Bales, and families moved from Adelphia and Phineas Hunt moved to Leescreek and Hardins Creek. To that same community, in 1803 moved, Jesse Baldwin, John Beals, Bowater Beals, John Evans, and their families.

Thereafter, meetings were held at various places, and by the year 1812, the Friends had been numerous enough in Ohio to form what is known as a yearly meeting, which is apparently something like a synod or a conference of some other denominations. Of this, the Perdew manuscript says:

In the year 1812, the writer of the foregoing account attended Baltimore yearly meeting, etc.

“At that time, Ohio yearly meeting was set off embracing the meetings belonging to Redstone Quarter, Pa., all the meetings in Ohio and the only meeting then in Indiana at White Water.

“The yearly meeting of Ohio was opened and held at Short Creek near Mt. Pleasant in the 8 mo. 1813.” Mr. Perdew also states that Sarah Beals, wife of Thomas Beals, “died on the 7th of the 7 mo., 1813, aged 89, and buried at Fairfield.” Gershom Perdew brings his narrative to a close with the simple statement, “Written by Gershom Perdew – 3 mo., 3, 1863.”

But, although he wrote at a comparatively recent date in the history of the country, it will be noted that he was an active participant in the affairs of the people about whom he wrote as early as 1812, and therefore, his memory must have gone back to the early days of the Quaker movement into the Old Northwest of which he writes so interestingly.

Thus we see that Quakerism, or more accurately, organized efforts of the Society of Friends, was first established in the Northwest Territory at Quaker Bottom on the present site of Proctorville, Ohio; from there, it spread to Salt Creek, now Richmond Dale, Ross County, Ohio, and then to Leesburg and Fairfield, Highland County, Ohio.

Also, we note that some Quakers settled at Highbanks, Ross County, Ohio, and some at Deerfield, in Morrow County, Ohio. Moreover, within a quarter of a century after the first meeting of Friends was held in the pioneer cabin of Jesse Baldwin, in Quaker Bottom, the Society of Friends had become an impressive religious organization in southern Ohio.

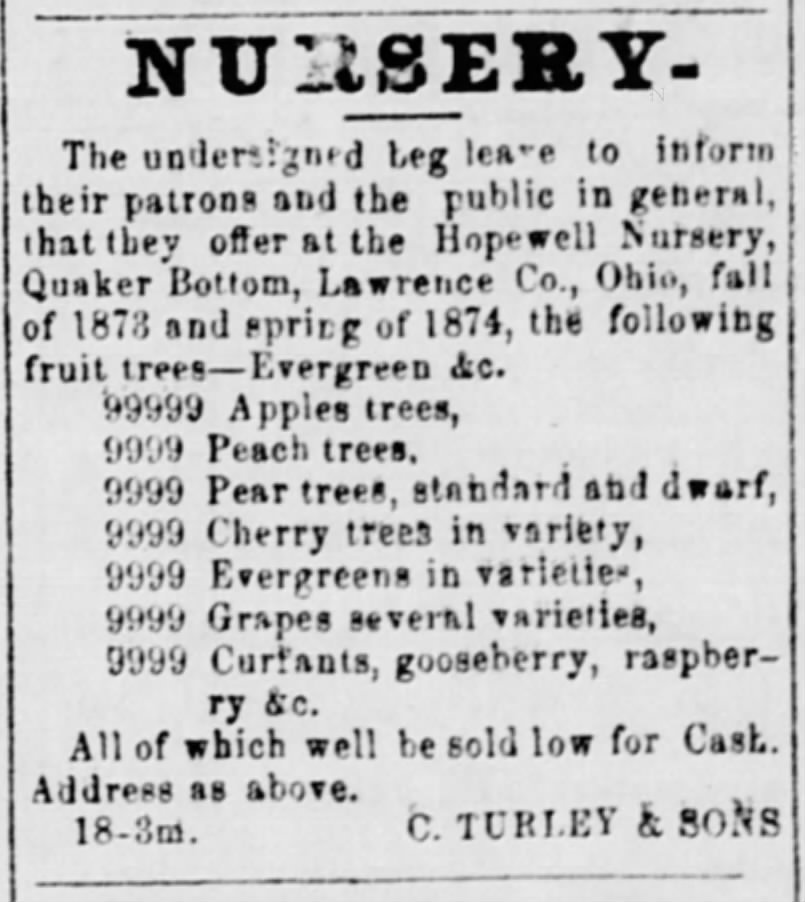

Huntington Herald Advertiser 20 Nov. 1873

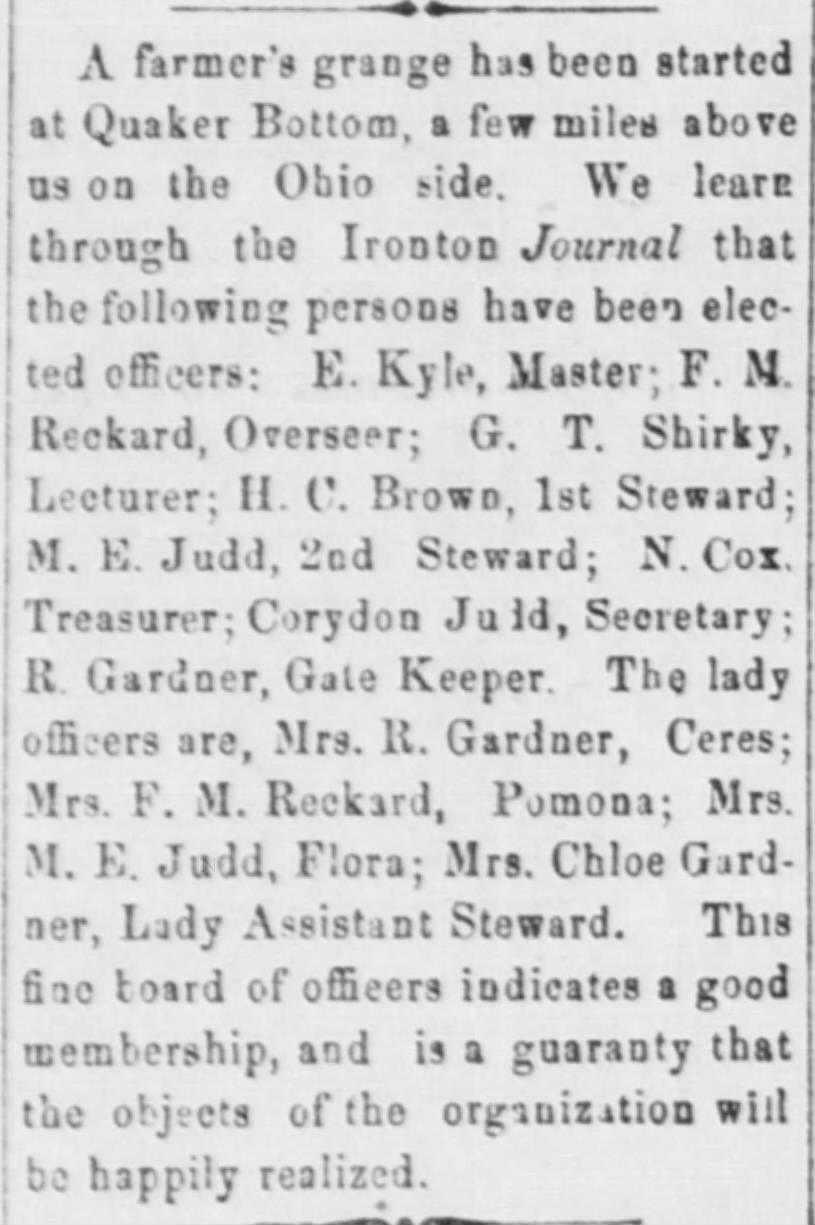

Herald Advertiser 8 Jan 1874

Shirley,

Thank you so much for your kind comment, when I received comments like yours it encourages me to keep adding more stories to The Lawrence Register.

Martha

I am so grateful for this publication. I have been trying to trace my family roots. My great grandfather was Perry Brumfield. He knew his parents came from PA and that he was a Quaker. He was born about 1845 and raised near Flag Springs, Lawrence Co., OH, where his parents had a farm. His mother died first, then his father, by the time he was 5 or 6. He had been taught to read and write by his parents. There were 2 other children but I do not know birth order. I think he was the baby. The children were taken to the slave auction at Ashland, KY and sold. Perry was purchased by a plantation owner in Mississippi and was a white slave for the next 15 years or so. He lived with the other slaves. For some reason he was allowed to keep his Quaker Bible and with it showed his black family the ABC’s and to read a little. During the Civil War, the slaves either escaped or were liberated. He joined the Union Army and served 2-3 yrs. until the end of the war. He returned to Lawrence County. He lived at Lecta, Waterloo, Wernicke, then Ironton, OH, where he died in 1945. This article helps me understand how and why a Quaker family would be living 20 miles up Symmes Creek from Proctorville, OH, all alone, with no other relatives or Quakers.