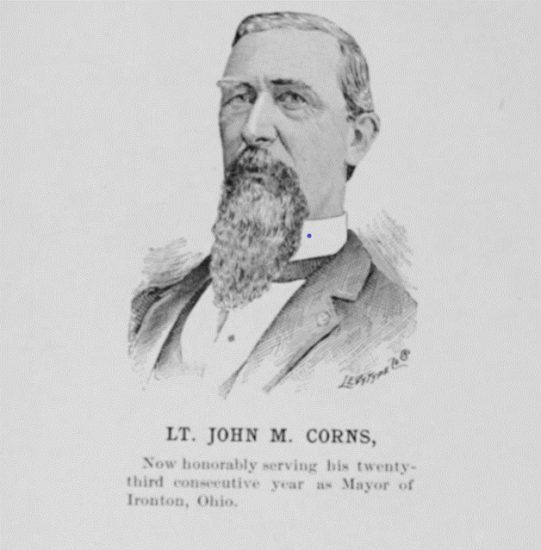

Mayor Corns War Experience

Narrow Escape #1

Ironton Register 18 Nov. 1886

Submitted by Peggy Wells

[Under the above head we propose to publish a series of articles, or rather interviews with old soldiers, giving details of narrow escapes while in the service. We will print them as long as the boys keep us posted with startling personal experiences or our interviewer can gather them in.– Ed. Reg.]

“What was your ‘narrow escape’ in the army?” we asked of Mayor Corns, of the old Second Va. Cavalry, as he stood smoking his morning stoga, before the big cannon stove of his office, last Monday.

“Oh, I had several that I thought were pretty narrow– narrow enough to make my flesh creep when I even think of them now.”

“But,” said we, “what was the little the worst fix you got into while serving Uncle Sam?”

“Well, sir, about the worst fix,” replied the Mayor, and he laughed and shuddered at the same time, “was when our division under Custer attacked Fitzhugh Lee, on the evening after the battle of Sailor’s Creek– that was the 7th of April, 1865, two days before the surrender at Appomattox.

“Lee was trying to get off with a big wagon train, and Custer had orders to intercept him and capture the train if possible. Just at nightfall, we caught up with Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry, down there not very far from Farmville. The enemy had gone into camp for the night.

They were in the woods and had thrown up piles of rails as protection against attack. We had a heavy line of skirmishes which were soon driven in, and then, having discovered the enemy’s line, Custer ordered a general charge. There was about 7000 cavalry and we went in with a rush, but after a bitter little fight, we were repulsed.

We ran into a ditch or drain in the charge and that upset our calculations. We piled into that ditch with considerable confusion and were glad to get out, without bringing any rebs with us. Our lines were soon reformed and another charge sounded. It was then after dark, but the moon was shining brightly. It was an open meadow over which we charged, and save the drain, was a pretty place for a cavalry fight, for those who liked that kind of business.

“After the charge was sounded and we were on a full gallop, lo and behold the enemy was charging too, and the two divisions of cavalry met in a hand-to-hand fight in the middle of the plain. It was an awfully mixed-up affair. We couldn’t tell friends from foe half the time. We had been on the go so much that our blue uniforms were dust-colored and about as gray as the rebels’. It was the biggest free fight ever I got into, and every fellow whacked away and tried to kill every fellow he came to.

“It happened, however, that I got in with a little squad of six or eight of our boys, and we kept together until we found ourselves completely within the enemy’s lines, with the rebs’ banging away all around us.

Our army was getting the best of the fight, and gradually pushing the rebs back, and of course, we went back with the rebel line. It looked scary to us. I saw Johnny Connelly near me and said to him, “This is a bad fix–we must get cut off this.” And he said, “Yes, and here are five or six others of us right near.”

I got them together, for I was a Lieutenant commanding a company, and said, “Boys, we must charge to the rear and join our army,” and one of the boys said, “Here goes,” and started, and we were all about to put after him, but just as I started, a reb who was just in front of me, and who I thought was one of our boys, whirled around and, drawing his saber, called out, “Surrender, you d—-d Yankee,” at the same time bringing the saber down toward my head with fearful velocity.

I dodged and the saber struck my shoulder but did not cut the flesh as I had on an overcoat with a bear-skin collar.

“The blade went right through these, but stopped at the flesh, but it paralyzed my arm, which fell to my side. He did it so quickly that I had no time to parry. But missing my head, he quickly drew his saber for another stroke, and I would have got it the next time clean through my head, but just as the reb had the saber at its full height for another blow, a First N. Y. Cavalryman struck his carbine right against the fellow’s head, and exclaiming “Not this time, Johnny,” blazed away and shot the reb.’s head just about off.

Then we scampered to the rear but hadn’t gone far when we got to the ragged edge of our own line and felt ourselves considerably safer. In getting out of there, three balls struck me, but I consider the narrowest escape, was when that New York Cavalryman stuck his carbine at the reb’s head and presented the blow which would have gone right through my head, as sure as fate. The narrowness of the escape was intensified by the fact that the war only lasted two days longer.

“Before we got out of there, Johnny Connelly was shot crazy, but I snatched his horse’s rein and got him within our lines. He was sent back to the field hospital and I never saw him since; but if ever I come across that N. Y. Cavalryman, I’ll take him home, set him down in the best rocking chair in the front parlor, and feed him on a mince pie and roast turkey as long as he lives.

“Well, we drove Fitzhugh Lee back, captured his camp, and got a great many prisoners, a large proportion of whom were drunk. We found applejack by the bucketfuls all through the camp, but we were not allowed to touch a drop, though my arm hurt me terribly bad.”

“Well, Mr. Corns, that was a”Narrow Escape.’”

“Narrow! Well, I should say so, and I sometimes have to feel up there to be sure my head ain’t split in two yet.”

0 Comments