Written by Wilma Fox

Poke Patch Station is gone. That fact did not stop our search from finding it.

Survival was especially harsh for people of color back in 1820 when Free Blacks settled in this community. Poke Patch was no more than an hour’s walk from the main road, now Ohio 93, and the nearby coal company town of Blackfork. But it might as well have been a hundred miles.

As a rule, white owners ran Appalachia’s industries back then. The good jobs went to those whose race was in power. Since White Ohio legislators made the laws, those laws were designed to keep Blacks under control and out of power. Without question, both industry and the law in Ohio treated the Black population with contempt as ignorant intruders.

Poke Patch was one of the first stations we visited. To test ideas for the long journey ahead, we rode throughout the area in August 1998, searching for signs of the former community. We found goodwill among the current residents but no reminders of the bygone community. Although Poke Patch harbored perhaps as many as two hundred fugitives, no signs remained of the community from the 1800s.

The old burial grounds have also been hidden by the passage of time. We learned that National Forest personnel seek its whereabouts. Stationmasters like John J. Steward and his wife are probably buried there, but the location eludes present-day hunters because of poor records and a lack of stone grave markers.

The old abolitionist residents died off, and generations later did so. The National Forest now owns and manages much of the land. Today the young people around Poke Patch must move away. The lack of jobs for current Black and White residents makes economic conditions a little better than they were for the abolitionists of the 1800s.

Nature has reclaimed the meadow near Dirtyface Creek below Negro Creek Road. Log cabins that once stood against the elements have succumbed to them. Time forever hides this once-active station’s tangible traces on the Underground Railroad. There’s poetic irony in hiding. Poke Patch once existed to hide its people. The community once concealed a spirit for freedom in this pokeweed-infested spot that gave it its name. Today only the round cluster of berries of the pokeweed nods its head of purple. The people and their struggles are long gone.

Ohio’s Black Laws, as they were called, required every Black or mulatto (a person with Black ancestors) who settled in the state to post a two-hundred-dollar bond. A newcomer had to register at the county seat and pay fees for all family members who settled here. Every Black had to produce a certificate from the U.S. Federal District Court certifying his or her free status.

If a Black failed to produce the certificate, he could not legally work even if certified. Blacks could not serve on a jury. They could not give evidence or testify. As the defendant, a Black person’s only witnesses would have to be White. Blacks were, in effect, bound and gagged by and in Ohio courts of law. And the great state of Ohio called itself a free state.

Those same laws affected the future of Black children who were denied an education and not allowed to attend school. Historians have written that these laws were passed to curb the migration of Blacks into Ohio from neighboring Slave States like Virginia (now West Virginia) and Kentucky. For Blacks who lived in Ohio or those who chose to run away to Ohio, these regulations almost certainly guaranteed a life of poverty and ignorance.

Not every Black man buckled under the oppression of such discriminatory laws. Some defied the laws outright. They learned to read and write. They worked. And secretly, they forged a network of safe places for fugitives, which became known as the Underground Railroad. One such man was John Parker, a former slave and active conductor from Ripley.

He wrote that the passage of the federal Fugitive Slave Law in 1850 forced fugitives and abolitionists everywhere in the nation to be more secretive than ever. This national law imposed severe penalties on anyone who came to the aid of a fugitive slave. It meant confiscation of property. It included a fine of up to one thousand dollars. And it meant a jail sentence of up to six months. It allowed the owner of a runaway slave to pursue his property wherever that fugitive went. The owner could arrest the slave and take him back home once he located him.

Joy and I were hunting our historical slaves, and the stations that harbored them long after the Civil War nullified the Fugitive Slave Law. We sought the locations of stations such as Poke Patch and wanted information about fugitives. No one was under any legal responsibility to help us, but help, they did. We discovered an atmosphere of neighborliness and cooperation among rural people of all colors. We were delighted at the residents’ and historians’ generosity and kindness in assisting us.

Stations like Poke Patch provided safe hiding places from slave hunters and the law. Conductors like Jacob Steward were knowledgeable guides through the area. Fugitives, sometimes referred to by code as “freight,” found shelter in or near the home of John J. Steward and his wife, the chief station keepers in the community.

Chief conductors out of Poke Patch were John’s brothers, one of whom was Jacob. It would seem that every resident of Poke Patch was involved in this clandestine protest against human bondage. Some of our information came from a book by Wilbur H. Siebert called The Mysteries of Ohio’s Underground Railroad, first published in 1951.

Professor Siebert sent his history students to their home counties across Ohio to gather data on the Underground Railroad in the late 1800s. Based on the letters these students collected, Siebert recorded the names of conductors, the routes they supposedly used, and the locations of stations throughout the state. Unfortunately, because it was published long after the time when the Underground Railroad flourished, it is criticized as not necessarily being accurate.

What we do know for sure is that conductors used a variety of methods to move freight to places like Poke Patch. False-bottomed wagons carried passengers unseen day or night, though the night was the safest time. Conductors near Getaway down in Lawrence County guided fugitives on foot westward along Rankins Creek under the dim light of a waning moon. At the intersection of another creek, the nervous party might veer north to follow the North Star. Fugitive slaves understood this instruction.

North was the principal direction in this region that led to the land of Canaan and freedom. Word among the fugitives in Lawrence County was to go north until they came to the valley of pokeberries. There they would be safe. No single road, main path, or one method identified this or any Underground Railroad route. Flexibility was the key to escape. Secrecy kept conductors safe from imprisonment and kept the whole of the Underground Railroad network a mystery.

Pursued by slave hunters, runaways bound for Poke Patch slipped across the Ohio River. We decided to start our journey on the Ohio side. The fugitives ran north, away from plantations in Kentucky and Virginia and from plantations deeper in the South. They rowed across the river in small boats concealed on the shore just for this purpose. Or they half-waded, half-swam, clinging to floating debris.

They left behind as quickly as possible the river with its ever-vigilant armed patrols. Anxiety, fear, and dangers filled their journeys on a desperate dash for freedom. Their goal was to get away from the hunters who they knew pursued them. Their strength and lives were sometimes taxed to the limit and sometimes beyond.

Negro Creek Road, now Washington Township 166, ran along a ridge in Lawrence County and stretched due north toward the community of Poke Patch. Before the Civil War, Poke Patch was simply a few cabins sheltered in a small valley overrun with pokeweed. Fugitives able to travel the twenty miles between the Ohio River and this tiny settlement in Gallia County might do so on one long day’s journey or by two nights of travel. What route a conductor with slaves or slaves alone took to get there depending upon conditions and the activities of slave hunters. We decided to make the journey in reverse.

We began our search in Poke Patch, then traveled south into more populated areas. But we, too, traveled a route designed to avoid contact with people and a present-day menace, vehicles. We wanted our horseback journey to be problem-free and as pleasant as possible. We did not want to face any of the dangers or hardships that awaited fugitives (or even the slave hunters) of long ago.

We selected Poke Patch because it served the area as a significant yet typical stop on the Underground Railroad. By the end of the Civil War, conductors like James Dicher and William Chavis had taken many fugitives through the community. Back then, the residents of Poke Patch believed in freedom to such an extent that they took great personal risks to aid these unknown refugees. James Dicher took perhaps eighty runaways to Poke Patch, following a railroad track part of the way.

Like many others in the area, this cleared right of way had been built to serve the thriving iron-making industry. One ran to nearby Mt. Vernon Furnace, built partly by abolitionist John Campbell and others. As mentioned earlier in this book, Campbell was an active supporter of the Underground Railroad. Following the path created by railroad builders, conductors on this train escaped much easier and faster on foot. At a landmark known to conductor Dicher, he would lead his party off the railroad bed near Poke Patch and scramble over hills and woods to settle.

Another conductor named William Chavis brought fugitives some thirty miles north to this remote pokeberry field from another station at Burlington down on the Ohio River. Runaways helped by these two men probably wore little more than the rags they were dressed in at the moment of their escape. With or without shoes, they ran. Whatever the weather conditions, they ran. Whatever hardships they faced, they kept traveling north.

Joy and I had the luxury of packing extra clean clothes for our trek. We had good boots to protect our feet from rain and mud or from painful occasions when one of our horses’ hooves might step on our toes. More importantly, we had horses to ride. Fugitives may not have worn any shoes even though they traveled by foot. We carried our food supply for the entire journey, a small backpacker’s stove to prepare hot meals, and a tent for protection from bad weather and bugs. I doubt the slave hunters would have been as comfortable. I’m certain the fugitives were not.

Lucky fugitives were sheltered and cared for by free Blacks like John J. Stewart and his wife, who hid them in or near their cabin in Poke Patch. As was the custom, they fed and clothed the travelers with whatever they could provide from their meager supplies. These stationmasters provided shelter if there was to be any, safe hiding for a little while, and a rare opportunity for rest. With this kind of help, most fugitives continued the journey toward freedom north of Ohio and outside the U.S.

Another Black, Cornelius Harris, was once a resident of this abolitionist hamlet. His great-granddaughter, Wilma Fox, believes he may have been a fugitive who ran as far as Poke Patch and then decided to stay. Wilma Fox lives today in nearby Ironton. A retired hospital clerk, she explained to me what little she knew of her great-grandfather’s life in an interview I had with her months before our ride. She’d heard from family stories that Harris and two siblings arrived in Poke Patch from the state of North Carolina in the 1800s before the Civil War.

Cornelius Harris, a brother named Lewis Marsh, and a sister named Telitha Marsh were the offspring of a union between Marsh, a plantation owner, and Harris, one of Marsh’s female slaves. Cornelius Harris took the name and the dark complexion of his mother. Telitha and Lewis chose the last name of their White father and were themselves light in color.

What brought the young Harris and his siblings to Poke Patch from North Carolina is a mystery to Fox and her family. Perhaps the answer was luck or perhaps circumstances. Fox turned to archives, census data, and whatever was available to find clues to her family history. One source she used was the Siebert book held on reserve at her local library.

Siebert’s research identified Peter Coker as one who arrived in Poke Patch in the 1840s. Coker secretly promoted the work of the Underground station over the years. Fox points out that Coker had a daughter named Elizabeth. This young girl, Elizabeth Coker, daughter of the abolitionist cited in Siebert’s book, married Cornelius Harris. The couple from Poke Patch history is Wilma Fox’s great-grandparents.

Absent from family stories about Elizabeth and Cornelius were any substantial details about Cornelius Harris’ life before residence in Poke Patch. Relatives’ lack of information suggested to Fox that Harris and his siblings might have been fugitives. The fear of being discovered as a fugitive slave would have been motivation enough to conceal his past from everyone.

Yet Harris remained in Poke Patch despite Ohio’s hostile laws and with the knowledge that if captured, he could be returned to slavery. Perhaps it was a pretty little Elizabeth that prevented him from moving on. Perhaps he had faith in the local Underground network members, believing that they might protect him from bondage as long as he remained hidden among the friendly folks in the valley of the Pokeweed in Gallia County.

Maybe places like Poke Patch, which were strategically located, offered the best defense against discovery and capture. Far from the centers of White government and law in the county seats, which were often centrally located, these remote areas were difficult to monitor and even more difficult to force to comply with the laws of the day. Regional historian of Black history, Michel Perdreau, has learned to look for Underground Railroad stations where the borders of three counties converge.

There he noted, are the locations of past Free Black communities. Among these distant settlements, far from the notice and clutches of White law, historians like Perdreau and slave hunters like us searched the secret stations for mysterious stories of conductors and slaves. Poke Patch once lay at the convergence of three Ohio counties, Gallia, Lawrence, and Jackson.

Joy and I were slave hunters looking for whatever remained visible. We hunted for the graves of the conductors who had defied the law for the sake of freedom. We found no unmarked graves. We hunted for the stations where fugitives were protected with sympathy and shelter. The buildings were gone. In places like Poke Patch, we found nothing. But we learned more than expected about the generosity and goodness of country people who live near there, some descendants of former slaves.

Pokeweeds still grow in the poor soil where at one time, the Underground Railroad thrived amid the poverty of one southeast Ohio settlement. Science long ago proved that pokeweed root was poisonous to humans, just as history long ago proved that The underground Railroad was poisonous to the institution of slavery. Many fugitives escaped in late summer and early autumn while pokeberries ripened to a deep purple.

The hard ground made it difficult for slave hunters to track them. Water in the creeks confused the hounds trailing their scent. Corn stood in fields ripe for eating. Someone somewhere secretly offered aid and sympathy. Eventually, violence erupted in the War Between the States. After many bloody years, both the War and the institution of slavery came to an end.

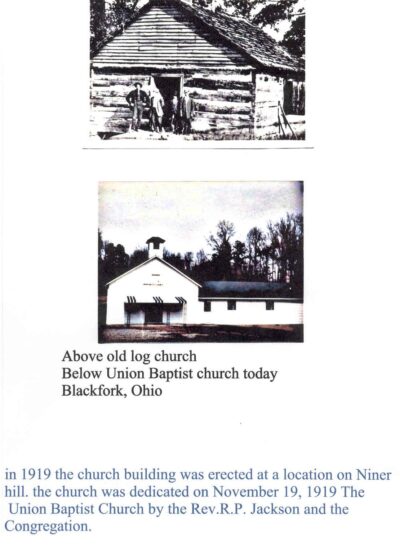

In 1879 the people of Poke Patch built a log church in the valley. There they joyously gave thanks for the spiritual blessings bestowed

upon them, which now included freedom. Near that, a cemetery received the bodies of the dead. Forty years passed, and by 1919 the log church had to be replaced. Church members built a new structure on top of Niner Hill overlooking the valley of pokeweeds.

This church, bigger, stronger, and more beautiful than its humble predecessor, radiates in testament to a surviving people. A photograph of the old log building hangs inside to remind members of the past. Though everything is gone, the log church, the cabins, conductors, stationmasters, and even their graves, the spirit of the Underground Railroad lives on. This new church was where we chose to begin our hunt.

Wilma Fox presented a letter of introduction from Joy and me to her cousin, Lee Keels, of Black Fork. Lee was the assistant clerk for the Union Baptist Church, the beautiful church on top of Niner Hill that replaced the old log structure in Poke Patch. Lee wrote back, permitting us to camp on or near the church grounds. She explained that the Wayne National Forest land came to the church property. This was an ideal spot to set up a base camp for the week.

Beyond the well-kept churchyard and the fenced-in cemetery, members of the church kept a small yard of forest property void of trees mowed off. Once we arrived with our horse, Joy and I strung up high lines in the woods to restrain the horses overnight. We stacked extra hay and gear along the edge of the woods in the yard and covered the hay with a bright blue tarp.

The Sunday twilight was clear and warm. A gentle breeze floated down into the valley. We had just tied the horses to the high lines, and before we had the tent unpacked, visitors began to arrive, church trustees Carlos Galliamore and Harold “Bus” Craddolph.

They had come to wish us well and brought their families with them. Carlos’ wife and daughter, Martha and Debbie, came in the Galliamore car. Harold arrived next, followed by Lee Keels and her husband, Lewis. Joy and I dropped our chores and spent some time visiting with our hosts while Joy’s husband, Don, snapped a few photos of our group.

Lee was amazed when darkness approached, and our spouses left us. She was not aware that two women alone planned to accomplish this journey. We assured her we felt quite safe. Each of us carried a cellular phone in our saddlebags in an emergency. We reminded Lee and Carlos that we carried their phone numbers if we needed their help. Little did we know that we would call for help before the week was gone.

The next twenty-four hours established our tempo for the rest of the week. We set up the tent within the fenced cemetery for protection from night critters. We ate our dinner by the light of the stars long after darkness had fallen. Then we slept until the morning light as soundly as the dead who lay beneath us. By the crack of noon the next day, we were saddled up and on the road.

We planned to ride a loop on Monday and return to our base camp, where we left our gear. The ride would allow us to get the horses used to each other and allow us to explore the Poke Patch area. The horse I brought was a big gray, twenty-four-year-old Appaloosa gelding I called Moose. He dwarfed Joy’s two ponies, Jacka, the Chincoteague pinto, and Pearl, the black Chinco-fino.

But Moose loved to explore new trails. He had as much energy and enthusiasm as the two young mares he followed most of the way, and he proved to be a perfect gentleman toward them on the ride. His one bad habit was playing ring around in circles when tied. No matter how tired or hot he was, whenever I gave him a break and tied him up, be it to a high line or a tree, he would prance round and round until his lead line would twist into a tight knot. Eventually, however, even this anxious behavior ceased once he got into the rhythm of our daily rides.

We wanted to find the tunnel James Dicher probably took fugitives through along the rail line to Poke Patch. But after we passed over the top of the tunnel (without realizing we had done so), we encountered a local man who advised us not to go down into it. He had heard there were many copperheads down there. By that, he meant snakes, not pro-slavery people. Access seemed difficult at best, so we noted the tunnel location on our map and rode away up Dry Ridge Road.

I was discovering things that the first day would not work well for the 2000 journey. I realized that Moose was not the horse for the long journey simply because of his age and size. He alone consumed as much grain and hay as the two ponies combined that Joy was training for the big ride and used this week. My notebook was also too big, even though it measured less than ten inches by eight inches. I needed to carry index cards or something small that would fit easily into my saddle bags or vest pocket.

Road maps were a nuisance from the back of a horse, and I was already thinking of laminating small segments of maps for the future. These would be weather resistant and could be more easily carried while riding. The smaller version would also not require folding and unfolding for use. I then realized the need to carry highlighters to mark our trail on the maps. The thought of carrying GPS equipment also crossed my mind briefly.

Phyllis Harris brought us water, fresh tomatoes, and cans of cold pop that evening in the churchyard. We felt very good about the day. The horses had behaved well in each other’s company. No one was thrown off or hurt. Strangers had been most helpful. We were looking forward to Tuesday when we would leave Union Baptist Church behind and set out to put some distance between it and our next stop. However, Tuesday turned into a disaster.

It was our first day out with the pack. Pearl was the designated packhorse for this trip, and we struggled to figure out the bright orange panniers Joy purchased. Although Joy wanted an early start, we weren’t on the trail until nearly 1:30 that afternoon. Would the crack of noon become the crack of midday? We had brought too much stuff.

Equally, packing the two sides of the panniers proved to be time-consuming and difficult. She would stuff a few items into one side and then stuff a few more into the other. But she always seemed to have an uneven load. One side would be heavier than the other, and she would have to start all over. Some things were too big to fit, like my red sleeping bag.

Eventually, I had to tie my blue duffel bag of clothes and my red sleeping bag to the saddle on Moose. That meant I had no room to ride and had to lead him on foot for the day. Also, the unbalanced overflow of stuff in an orange bag swinging from the saddle horn on Moose caused the saddle to slip under him. I was repacking before two o’clock.

Walking on foot, I slowed the horses considerably and reduced the miles we could cover that day. In addition, it turned out to be blisteringly hot. The humidity was high, and the sun relentlessly beat down on my back. I felt hot Moose breath on my neck with every sweaty step. Moose had a bad habit of walking with his nose against my back. In the heat, this trait proved most annoying. I felt as if I spent most of the miserable day shaking my lead line in a fruitless attempt to signal Moose to back off.

As the day began to close, Joy spoke to a young man named Charles Chambers, who lived on Dry Ridge Road. He directed us to a campsite in the Wayne National Forest back a mile or so in the direction we had come. Charles was a natural resources student at Hocking. College, where I worked, and hoped his training would get him a job with the National Forest that surrounded his family’s home.

This kind young man watered our horses and took our overloaded supplies so I could ride Moose up the ridge to the campsite. While we rode up the hill to find the turnoff to the campsite, he drove to the Union Baptist Church and brought back some hay for the horses. We assembled the tent on a soft carpet of pine needles amid towering pines.

We high-lined the horses and fed them plenty of hay, grain, and water, thanks to Charles. That night we fell asleep inside the tent as a heavy rainstorm came and washed off our dirty horses. The next morning we awoke to thick fog drifting among the pines and somewhat cooler temperatures.

Joy repacked the Panniers on Pearl. She could layer my sleeping bag inside the roll across the top of Pearl. I again tied the blue duffel behind my saddle and dangled the orange bag of food from the saddle horn. The change in what got packed by Pearl and what I had to carry on Moose allowed some space in the saddle for me to ride. I was grateful.

I had come to understand one reason why a person on foot might prefer to travel by moonlight to the summer sun’s heat. It had nothing to do with avoiding people. Joy cut a few minutes off packing time, and we were on the trail by 12:40. This late start every day bothered me. I would have liked to start the ride as early as seven.

Ride for three hours. Rest the horses over the hottest hours of the day. Then resume the ride traveling into the dusk and cooler evening hours. But packing problems wouldn’t allow it. I needed another alternative. But what alternative to packing a horse? I didn’t know right then.

We rode along quiet township roads most of that day and only encountered one vehicle. Later in the afternoon, we turned down Mt. Vernon Road, so named because of the nearby Mt. Vernon Furnace. The car traffic picked up almost at once. Because we had been riding on a ridge top, we had not found water for the horses to drink since morning. When we came to Littles Cemetery, they were thirsty, though not dehydrated.

We had always walked the horses, and they had passed through the shade for much of the trip. But it was time to use cell phones and call for help. Wouldn’t you know it, my cell phone battery was dead! Fortunately, Joy’s phone was charged and working.

Joy called Carlos about our predicament. He gave us John Boyd’s number, and she then called him. John brought us a huge tank of water in the back of his truck within the hour. Together he and Carlos dropped the heavy plastic barrel from the tailgate onto the ground at Littles Cemetery. We were saved. Soon the horses had their fill. We had enough water to make dinner, clean ourselves up a bit, and still had plenty left for the horses to drink through the night and into the morning.

Slave hunters of the past would not have been so cheerfully aided if their horses had been thirsty. Certainly, their horses would probably have received humane treatment from the locals. But I seriously doubted if any Poke Patch community member would have gone out of their way like John and Carlos did to assist the humans. Then I wondered about the fugitives, fearful of turning to strangers for something as simple as water, afraid that the hand that offered a pitcher of cold liquid could also be the hand that legally bound them back into slavery.

The fact that we had a need, one as basic as water, pointed out the necessity for a backup crew or a support vehicle. Although I knew that Joy wanted to rely on luck for the sake of adventure, I felt we needed to protect our horses and see to their comfort if there were any means possible. I figured my old truck was the means possible.

It could haul the hay and water for the horses, as well as our food and maybe electronic equipment. It was something to think about and discuss. All I had to do was find a driver willing to spend most of her days alone, support us in whatever needs became apparent along the way, and do this labor for free. I shuddered at the thought that I had just described our need for a slave.

The next day, we met Diane McKenzie at her farm near Zion Church. Joy offered to pay her if she would bring us two bales of hay and some water for the horses at the Johns Creek Trailhead at Vesuvius State Park that night. Diane’s family was composed of horse owners, and she knew exactly what we needed and agreed to Joy’s offer.

When we arrived at the trailhead, Diane and her family were waiting for us. They told us about two choices they were familiar with for camping. One spot was in a small area at the base of the water tower, and the other was in the field a little distance away.

Once we saw the lush grass of the open meadow, there was no question where we would stay. The horses must have thought they’d walked to Heaven and at once set about grazing. Jim McKenzie, Diane’s husband, carried a bale of hay in one hand and one side of a water container in the other.

I carried the other side of the container. The water weighed so heavily that the handle cut off the circulation in my fingers. It took all my willpower to maintain my grip. Their young daughter, Anna, carried a full 5-gallon collapsible water jug. The Mackenzies then refused to accept any payment for their services.

With the arrival of Friday morning, our ride was about over. We planned to explore the Vesuvius horse trails, leaving our gear in camp for the day. Our husbands knew to pick us up at this site on Saturday, so there was nowhere else we needed to travel to. We could have some fun riding in the woods. We learned much about what we needed to do to prepare for our future adventure.

Packing a horse caused too many delays. Perhaps a backup or support crew would solve that problem. We realized that once on our journey, we would need to be flexible and able to adjust our path to the circumstances that presented themselves.

We would need to be as adaptable as the elusive slaves we tracked. We also realized that we would need help from strangers to succeed. In effect, we needed present-day conductors and stationmasters.

When all they had was each other, it’s little wonder that the long tradition of Blacks helping Blacks sustained settlers and fugitives in a time and place when little else did.

The helping tradition, which supported the fugitives who passed through Ohio on their way to Canada, is still alive. The residents of Blackfork and the members of the Union Baptist Church were our stationmasters on this journey.

They maintained that spirit of generosity and helpfulness and extended it to us. Unsuccessful hunters that we were, we discovered, as have historical researchers and descendants, that the tangible evidence of the Underground Railroad continues to evade those who hunt for it. The spirit, however, lives on in the stories of former slaves and the generosity of their children’s children.

Author’s note: This chapter and the next were written from notes gathered on rides completed in 1998 and 1999. What appears here may not be part of the final book in this exact form. As we ride in 2000 from Ripley, Ohio to Canada, more present-day conductors, former Underground Railroad stations, and our reflections on those experiences will impact and alter content as appears here in these proposal chapters.

Thank you, Jason! Do you live in Lawrence County, Ohio? My son has a friend named Jason Harris, just wondering if there was any connection.

Martha

Hello I am Cornelius Harris grandson Jason Harris not many of us left

Google “Saponi Nation of Ohio”;the majority of the “core” names are [the] aforementioned names etc.

Cornelius Harris,and Elizabeth Coker were my great,great grandparents;the parents of my great grandmother Laura Harris; I have her birth certificate and it says that she was “white”;Scott,Keels,Harris,Coker,Marsh,Stewart,and others were [all] Saponi; too much [mis]information documented.

Sonia,

You are so welcome and thank you for taking the time to comment and leave your story for others.

Have a wonderful day,

Martha

Beautiful, Searching for Poke Patch. I grew up in Blackfork Ohio. Myself and several cousins call ourselves the last generation. I remember riding my motor cycle up Niner Hill during the summer months and how I always knew I was in sacred ground. Thank you

Sonia Scott