More Refugees of the Revolution

The Herald-Advertiser, November 27, 1938

Submitted by Brenda McClaskey Cook

By R. C. Hall, Ph. D.

Here are Reviewed the Trials, Tribulations, And Rewards That Came To Those Immigrants From Canada And Nova Scotia

Some time ago we discussed, in these columns, the emigrants of the American Revolutionary war, that is, those Tories who went out from the United States to find more congenial homes in Canada or Nova Scotia.

We suggested then that we might, at some other time, present the other side of the picture, namely, the story of the immigrants of that struggle, this is, those Whig Canadians and Nova Scotians, who sought refuge in this country from treatment, not to say persecution of their fellow citizens at home.

This is perhaps as good a time as any to tell this story. In fact, it appears quite appropriate, just at this period of our history to consider any subject dealing with minorities, persecution, emigration, immigration, or general migration, in fact, with any subject dealing with citizenship in a country where the rulers are intolerant of all opposition.

In our previous sketch, to which we have just referred, we made plain – we hope – what brought about the emigration of the American Tories. And, of course, it was the same thing, from an opposite standpoint, that brought about the immigration of the Canadian Whigs. But to sum up these reasons briefly:

Not everyone in the 13 original United States sympathized with the revolutionary governments of these states while not, everyone in Canada and the other British colonies sympathized with the efforts of Great Britain to conquer the new state governments and for the 13 colonies back to their allegiance to Great Britain.

Hard To Be Fair

In each instance, of course, these minority groups became subject to the derision, dislike, and contempt of their fellow citizens of the majority. Under such conditions, even in times of peace, it is difficult for people to restrain their feelings and or governments to maintain order with fairness and justice to all, but, in times of war, this is almost impossible.

The constituted authorities in the United State grew more and more suspicious of all Tories for fear they would contribute substantial aid to the enemy, while the British government likewise became more and more suspicious of the Whigs. Under such circumstances, each government adopted, as the conflict went on, more and more restrictive measures to deal with these respective groups.

It was almost inevitable, under these conditions, that some unfortunate acts should occur that kept these citizens unsympathetic to their government’s aims in an almost constant state of alarm. Now there appears no substantial evidence to warrant the conclusion that this persecution of minorities, in this country or in the British provinces, ever attained the cruel proportions which are said to characterize the persecution of certain groups in foreign lands today. Neither the Tories in the Unites nor the Whigs in British America were subject to wholesale persecution.

That is, they were confronted neither by the headsman nor the concentration camp, neither by execution nor imprisonment, except in those cases where there was clear and almost indisputable evidence that they had committed acts which, according to the universally accepted principles of international law, came under the heading of reason, such as lending military assistance to the enemy, committing acts of sabotage, spying, etc.

Nevertheless, the condition of these respective groups must have been very uncomfortable and at times alarming. Had we no other evidence of this except the fact that comparatively large numbers of each group migrated into the country of the other, this alone would certainly be evidence enough to warrant such a conclusion.

Men do not usually leave the land of their birth without a very substantial reason. Certainly, they do not usually pull up stakes, as the saying goes, abandon their possessions and wealth, take their families and go into another country and give their allegiance to a foreign nation without what appears to them at least, to be a very good and sufficient reason.

And so, the bare fact that many Tories fled from the United States during the Revolutionary war is certainly ample evidence that they were treated indulgently by the constituted authorities, to say the least. And the same may be said of the British refugees who sought haven in the United States at the same time.

Of course, most people in the United States today will perhaps prefer to believe that the condition of the latter was much worse than that of the former. And while this is a poor excuse and no reason for the colonial attitude on the subject, there does appear to be some truth in it.

Colonies Were Poor

Of course, one thing that made the condition of the British refugees in the United States somewhat worse than that of the American refugees in the British possessions was the fact that the United States was not prepared to take care of her immigrant friends whereas the rich and powerful government of Great Britain was amply able to make provision for the temporal welfare of many more than fled to her for protection.

Moreover, the English showed a commendable attitude toward these unfortunate and perhaps did all that was within the power of government to provide for their comfort and happiness. But the United States, hard-pressed to establish its own independence, paid all too little attention to these loyal supporters and friends who had sacrificed almost everything but life itself on behalf of liberty.

Some actually sacrificed their lives for the cause as they enlisted in the armed forces of the revolting colonies. And this was another reason, perhaps, that the condition of the British refugees was harder than that of the American ones.

The fact that many of them, or members of their families, actually took up arms against Great Britain, gave the English government an excuse to adopt a straight military attitude toward all such that it could apprehend. Of course, the same might be said for the other class, but just as the British were more able than the Americans to reward their friends, so they were more able to apprehend and punish their enemies.

Another view of the situation I not very flattering to the Americans, and that is their apparent lack of appreciation for the really valuable services rendered to them by some of these refugees from Canada.

Colonel Livingston

The government gladly accepted these services but apparently without any thought that they deserved any special recognition. Of course, this resulted largely from the exigencies of the situation at the time and was largely remedied, so far as possible, at a later date, as we hope to show a little further on in this sketch.

Perhaps the most outstanding example of British refugees to the United States was Colonel James Livingston. He came from the Livingston family of New York and New Jersey and was a native of the state of New York. He had, however, become an attorney and settled in Montreal to practice his profession. But like his relatives farther south, he was a firm believer in the principles of the revolutionists.

And right here we find, perhaps, the chief explanation of the attitude of the Tories in this country as well as the Whigs across the border. In other words, most of the Tories were either members of the Church of England, officials of the English government, wealthy persons who feared the loss of their property, members of families with relatives in England, or persons in other ways closely tied to England by business or sentiment, whereas the revolutionary sympathizers in Canada and Nova Scotia were mostly emigrants from the southern colonies, or related to families in the United States, or in some other way linked with the aspirations and principles of the democratic movement.

As the dominant party in each section of the country (the United States and Canada) desired the conquest of the other section, it naturally availed itself of its friends there to assist it.

Assault on Canada

Thus when, in the summer of 1775, the leaders of the revolutionary movement in the 13 colonies decided to send an expedition against the loyalists in Canada in an attempt to overthrow the British government there, they were naturally glad to avail themselves of the help of such an able and enthusiastic supporter as Colonel Livingston.

Generals Schuyler and Montgomery undertook this expedition but due to the poor health of the former, General Montgomery became the actual commander of the undertaking.

Generals Schuyler and Montgomery undertook this expedition but due to the poor health of the former, General Montgomery became the actual commander of the undertaking. But General Montgomery’s wife was a member of the Livingstone family, and here again, we find one of the common ties that existed between some families on both sides of the international border.

Such ties, of course, did not always bring about unity of action but they were doubtless responsible for much of the unity of action that did occur on both sides of the line.

At any rate, Colonel Livingston wasted no time in aligning himself with the revolutionary party and now, upon learning of the proposed Montgomery expedition, he hastened to recruit a band of Canadian patriots to cooperate with it.

By dint of great energy, he succeeded in enlisting something like 400 men, mostly from the Montreal vicinity, who he led across the border to join Montgomery, and who had the satisfaction of later helping capture their hometown, as well as St. Johns and other places along the border in behalf of what was soon to become the new government of the United States. Moreover, many of these refugees were fighting with Montgomery when he fell to Quebec on the last day of 1775.

Rewards Offered

As we have suggested, the officials of the revolutionary movement in the 13 colonies were far too preoccupied to do anything for their Canadian friends for a time and perhaps they might never have done much for them had it not been for the action of the British government in offering rewards for desertion from the continental forces to their side.

The Tories had convinced them that the loyalists in the colonies were of sufficient number and strength to weaken the revolutionary movement to the point where it could be easily crushed, with the proper encouragement to them – the Tories – to take open action. And so, the British government issued a proclamation, in 1776, inviting desertion from the Colonial army and offering substantial rewards to such deserters as complied with the requirements set forth in the offer.

As a result, it has been claimed that over 2,000 deserted and joined the British in Philadelphia alone. And while this claim may be somewhat exaggerated, it appears certain that the glittering offer of gold was too great a temptation for many a lukewarm patriot to withstand, to say nothing of the sincere Tories.

To combat this act of the British, the Continental Congress was influenced to pass a similar act which was in part as follows: “that this congress shall give to all such of the said foreign officers, as shall leave the armies of his Britannic majesty in America, and choose to become citizens of these states, unappropriated lands, in the following quantities and proportions, to them and their heirs in absolute dominion.

To a colonel, 1,000 acres; to a lieutenant colonel, 800 acres; to a major, 600 acres; to a captain, 400 acres; to a lieutenant, 300 acres; to an ensign, 200 acres; to every non-commissioned officer, 100 acres, and to every officer or person employed in the said foreign corps and whose office or employment is not here specifically named, in the like proportion to their rank or pay in the said corps.”

Basis of U. S. Plan

This act passed, on August 14, 1776, may be said to have formed the beginning and basis of the plan later adopted somewhat more specifically or rewarding or at least compensating in some degree the friendly and loyal British supporters of the revolution and the early government of the United States. However, this first attempt in this direction proved pretty much of a failure due to its lack of acceptance on the part of almost all of the refugees.

As a matter of fact, it appears that only one single individual came forward to claim this reward.

Now, please do not mistake this fact. This does not mean that none of the refugees from Canada ever accepted compensation for their loyalty to the United States. Quite a few did, as we shall note later in this sketch. But only one deserter from the British army claimed the reward offered for such an act. It appears that, on March 27, 1792, the congress passed an act reading in part thus: “That there be granted to Nicholas Ferdinand Westfall who left the British service and joined the army of the United State, during the late war, 100 acres of unappropriated land in the western territory of the United States, free of all charge.”

Treated as Traitors

But although this appears to be the only instance of its kind, there were many like Colonel Livingston and his recruits who had from the beginning of the revolutionary movement sided with the Colonial patriots and were in no sense deserters from the British army. However, they and their families and associates in many instances were treated by the British as traitors during the war and afterward as outlaws, it appears.

At any rate, after the disastrous affair at Quebec, Colonel Livingston withdrew from Canada to New York and served as a colonel in the American army throughout the Revolutionary war. His troops were other Canadians, who like himself dared not return to their native land during the war and who would not have found a very congenial reception there for years afterward if indeed it would ever have been safe for them to have tried to return.

Then too, most of them, or their parents perhaps, were originally citizens of the colony of New York, or one of the New England colonies so that, under the circumstances, they probably found the United State more to their liking anyway. Nevertheless, this country, after the war, was confronted with the necessity of doing something for this group or else appearing rather ungrateful for the real sacrifices it had made on behalf of liberty, freedom, and American nationality.

These British refugees had one consolation, however, which was denied to the American fugitive Tories, and that was a success for the cause for which they sacrificed so nobly.

Congress Rewards

Nevertheless, the British government, as we have noted, promptly and apparently, for the most part, made ample provision for the welfare of the fugitive Tories, whereas the United States let the matter of providing for the refugee British drift until April 23, 1783, when congress passed the following resolution:

- “Resolved, that the memorialist be informed that congress retains a lively sense of the services the Canadian officers and men have rendered the United States and that they are seriously disposed to reward them for their virtuous sufferings in the cause of Liberty.

- “That they are further informed that whenever congress can consistently make grants of land they will reward in this way as far as may be consistent the officers, men and other refugees from Canada.”

Thus it will be noted that it was not until near the end of the war that official recognition was made of the debt the government owed this group and even then not until urged from without by a “memorialist,” and furthermore only in the vaguest and uncertain terms as to what could be done about it.

It was about two years before the matter was seriously considered again, and then only by the passage of an act on April 13, 1785, placing the refugees from Nova Scotia on the same basis as those from Canada.

But, although congress did thus express its goodwill toward these groups, there was little else it could do about the matter. It had neither money nor lands with which to reward them.

After War Ended

But after the close of the war, it began to look like something might be done for them in the way of granting them certain western lands as several of the colonies extended westward to the Mississippi river and thus had thousands of acres of western unsettled and unowned by private individuals. But these tracts belonged to various states and not to the nation itself.

Moreover, some states had more than others. But when these lands were ceded to the federal government, the Congress of the United States found itself in a position to fulfill the promise made by its predecessor, the Continental Congress and the Congress of the Confederation. Finally, on April 7, 1798, congress passed an act, in part as follows.

- “Section 1. Resolved that satisfy the claims of certain persons claiming lands under certain resolutions of congress, of the twenty-third of April, one thousand seven hundred and eighty-three, and the thirteenth of April, one thousand seven hundred and eighty-five, as refugees from the British provinces of Canada and Nova Scotia, the secretary of the department of war be, and is hereby, authorized to direct, to give notice, in one or more of the public papers of each of the states of Vermont, Massachusetts, New York, New Hampshire and (missing) tions, to transmit to the war office, within two years after passing of this act, a just and true account of their claims to the bounty of congress.”

This act further provided that no one should receive lands under its provisions except those described in it or their heirs, and describes the legal claimants as follows:

- “First, those heads of families and single persons, not members of any such families, who were residents in one of the provinces aforesaid, prior to the fourth day of July, one thousand seven hundred and seventy-six and who abandoned their settlements in consequence of having given aid to the United States or colonies, in the Revolutionary war against Great Britain, or with the intention to give such aid, continued in the United States, or in their service, during the said war, and did not return to reside in the dominions of the King of Great Britain prior to the twenty-fifth of November, one thousand seven hundred and eighty-three.

- Secondly, the widows and heirs of all such persons as were actually residents, as aforesaid, who abandoned their settlements as aforesaid, and died within the United States, and who during the war, entered into their service.” Nevertheless, it was not until 18 years after the close of the war that congress made actual provisions for rewarding these refugees. But finally, on Feb. 18, 1801, an act was passed reading in part thus:

- “Sec 1. That the surveyor general is, and he is hereby, directed to cause those fractional townships of the sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, nineteenth, twentieth, twenty-first, and twenty-second ranges of townships, which join the southern boundary line of the military lands, to be subdivided into half sections, containing three hundred and twenty acres each; and to return a survey and description of the same to the secretary of the treasury, on or before the first Monday of December next; and that the said lands be, and they are hereby, set apart and reserved for the purpose of satisfying the claims of persons entitled to lands under the acts, entitled ‘An act for the relief of the Refugees from the British provinces of Canada and Nova Scotia.’ “

Location of Tract

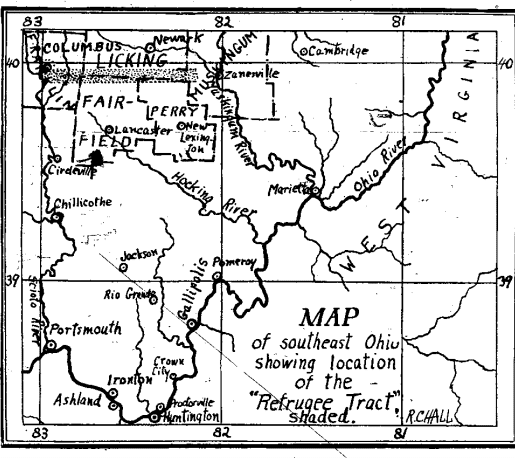

The location of the tract thus set aside and donated to the refugees from Canada and Nova Scotia will be best understood by the reader, perhaps, if he or she pictures it as a narrow strip of land four and one-half miles wide extending eastward from the Scioto river far enough to include about 136,000 acres of land and with its western extremity lying within the present city of Columbus, Ohio.

And now that its approximate location is perhaps clearly understood its approximate definite boundaries and limits may be given a little more clearly in terms of present-day place names by saying that the tract extended north and south from Fifth avenue to Steelton streets in Columbus and west to east from the Scioto river, across Montgomery and Truro townships, Franklin county, on across the southern part of Licking county and the northern parts of Fairfield and Perry counties and on into Muskingum county, a distance of about 48 miles altogether.

The Refugee Tract, as this strip of land, is known did not prove especially popular, it appears, with those for whom it was set apart, as only about 50 claims amounting to 45,282 acres, were made under the Act of 1798 which permitted the claims to be filed I advance of the selection of the tract.

The Refugee Tract, as this strip of land, is known did not prove especially popular, it appears, with those for whom it was set apart, as only about 50 claims amounting to 45,282 acres, were made under the Act of 1798 which permitted the claims to be filed I advance of the selection of the tract.

However, it should perhaps be pointed out that at that time no one knew what provisions would be made for the refugees or whether or not any satisfactory arrangement would ever be made for their compensation for their patriotic sacrifices.

And even if they did have enough confidence in the government to believe that they would ultimately receive lands they had no way of knowing if these lands would ever be of much actual cash value.

Already Had Homes

Then too, by the time the grant was actually made, many of those with valid claims had already been long established in homes in the east and had no desire to come west to a wilderness practically uninhabited and which could be reached only by a long and arduous journey.

Moreover, many of the original claimants or those who might have made valid claims had passed away and their claims descended to their heirs. Quite a number of these, with perhaps a few of the original claimants, once the lands were available, accepted them and settled on them. Others simply sold their claims at almost any price to speculators or young people who wished to try and make a fortune in the west.

It is interesting to learn that some of the descendants of refugees were found to be living on this tract after the passage of a century from the time it was granted to their ancestors. For instance, Colonel James Livingston was one of the original proprietors of lands on this tract having received the original patents to certain amounts. These lands passed by inheritance to the colonel’s son, Judge Edward C. Livingston, and then in turn, to the latter’s son, Robert N. Livingston.

But no doubt by far the greater portion of the people dwelling today on the Refugee Tract are totally ignorant of the interesting history attached to the lands they own or occupy. Probably not one in ten of the residents of that part of the city of Columbus located on this tract know that the title to their home sites rests upon this grant made by the Congress of the United States to the immigrant refugees from Canada and Nova Scotia so long ago.

Once Military Tract

After reaching the eastern limits of what is now Franklin county, Ohio, this tract extends eastward across the southern part of Licking county, the northern parts of Fairfield and Perry counties, and on into Muskingum county. It had originally been a part of the United States Military Tract and the Congress Lands. As both of these tracts were government lands, the former being simply reserved for the payment of certain military claims, the government was at liberty to set aside certain amounts for certain purposes such as the Refugee Tract.

Two and a half miles of the width of this strip came off of the Military tract and as the southern boundary of this tract was taken as the southern boundary of Licking county, the remainder of the Refugee Tract in the section came off of the counties to the south of that line, namely Fairfield and Perry counties respectively.

The value of the land on the Refugee Tract was later greatly enhanced by the National road which ran practically its entire length from the Scioto river to Hopewell township, in Muskingum county, where the Refugee Tract ended shortly east of Gratiot.

This village is located on the boundary between Licking and Muskingum counties, so the Refugee Tract actually extended but a very short distance into Muskingum county. It was originally intended that it should reach the Scioto river to the Muskingum river.

5,000 Acres for Schools

Apparently, however, most of the refugees or their heirs, who accepted and took up land on this tract did so in what now forms Franklin and Licking counties and as few claims were made for land farther east, the tract, as such, was never surveyed and opened up to refugee settlement farther east than indicated.

This land was divided into 69 parts, amounting to 65,280 acres, to which were added seven sections, or about 5,000 additional acres, which the congress gave to the inhabitants for the purposes of schools.

Thus the amount of land set aside for these refugees amounted to approximately 70,000 acres, in one of the finest locations in the country. It was on Jan. 3, 1802, that the locations were made, according to law, and patents of ownership were promptly issued to those claimants who had made and established valid claims under the various act of congress regarding the matter.

Thus, after so long a time, the United States finally discharged its (end of the article is missing).

0 Comments