Wire and Wire Products, Jan. 1949, Vol. 24, #1

54 Years in the Wire Business by C. L. McGowan, Superintendent Wire Mills Atlantic Steel Company Atlantic, Ga.

The Mordica Memorial Lecture, 1948

Among the old-time Irish there was a strong belief that those near and dear to one never actually departed this earth. Get a group of friends together and start remembering some of the gay and happy times enjoyed with the deceased and sure enough, one of the assembled companies would feel a light touch on the cheek like a fragile kiss or hear a bit of sweet music.

This indicated to one and all that the lost one was close by and glad to know that he or she was remembered by those left behind. Of course, the ideal place to hold such a session was in surroundings familiar to the person who had gone beyond.

If that old superstition had an iota of truth in it, surely one of us assembled here will feel a light touch on the cheek or hear that sweet music for we are gathered in a spot that held many memories for the man in whose honor we go back half a century to reminisce on days gone by in which he played his pioneering role. If the spirit of John Mordica could roam about at will, I am sure that he would be with us today—and perhaps he is!

I was less than 50 miles from this very spot when I first met Johnny Carter. His folks and mine were neighbors in New Castle, Pennsylvania. John himself was about 16 years old when I first knew him in my pre-school days. There were numerous Carter kids and numerous McGowan kids and we all played together. My brothers and his brothers were good friends and my mother always spoke of Mrs. Carter as a “good neighbor.” Mr. Carter, like my father, was in the wire business, and in those days, it meant moving from place to place, so after a few years my family moved to another town, the Carters moved some- where else and it wasn’t until 1900 that I met Johnny Carter again.

One day I was working at Belfont a fellow I knew from Kelly’s Mill asked if I knew a John Mordica who was also from New Castle. Imagine my surprise on meeting Mordica to find out that it was my old friend, Johnny Carter. Now a married man, he was using his own surname. In our boyhood days, he had gone by his stepfather’s name due to the extreme devotion that existed between the two. All of his life John Mordica was devoted to his stepfather and no natural son and father have ever been closer than these two were. John at this time was working, as I said, at Kelly’s Mill and I was at Belfont. Contrary to belief we never worked in the same mill.

After our days in Ironton, Ohio, I went on to Peoria and John moved to Ashland, Kentucky, then on to Kenova, West Virginia, and finally to Johnstown. During the years we had many a friendly reunion and always managed to keep in close touch with each other from that day on.

When John was first beginning his plans for organizing the Wire Association, I happened to run into him one day in this same hotel. He told me his dream and I remember telling him that I didn’t think it would work. I was convinced that the men in the wire business could never get together on a common meeting ground. My reason for feeling this way was because of the fact that most of the old-timers like John and myself had learned our lessons the hard way. We had no textbooks from which to get our formulas.

In the early days, you couldn’t get a course in two or four years that would teach you the fundamentals of the wire business. When we were coming up, it was like pulling teeth to get an old-timer to tell you anything. Their stock answer was “No one told me.” I assured John that he could count on me as a charter member, but I was afraid he would encounter resistance from others in the industry. How wrong I was

and how right he was is amply proved by this assembly today. The Wire Association was formally organized here in this hotel within a year, and today is a living memorial to John Mordica.

The best way I know to give you a picture of what went on in the wire business from the time I first met John Carter in New Castle until the formation of the Association is to tell you my own story of 54 years in the Wire business, which is pretty much a duplication of the experience John Mordica could relate to you if he were here today. Like him, I started a long, long time ago.

I was literally born into the wire business. Despite my Southern accent, my early boyhood was spent within 50 miles of Pittsburgh. The first mill I can remember was the nail mill of the Hartman Steel Company and the keg shop of Edwin Bell and Son at Beaver Falls, about 30 miles west of here. My uncle, J. C. Maloney, was superintendent of the nail mill there and my father had the cleaning, packing, sorting, and shipping departments of the nail mill. Three other uncles were in the nail mill while my grandfather, another uncle, and a cousin worked in the wire mill and still another uncle in the rod mill. While I never worked in that mill, I made many a visit to it. In later years I did work at the keg factory for five cents an hour—ten hours a day!

About 1887 a new mill was opened in New Castle and many of the men from Beaver Falls, including some of the members of my family, moved there. Among the men who came to New Castle, when the mill opened, was Peter Senior was day boss of the mill. His son Tom was the night boss, and our own Peter Igoe was the cleaning and packing department. Another old-timer, George Paff, was I believe, a millwright at New Castle.

When Cleveland was serving his second term as President and the panic of 1892 hit, combined with the tragic Homestead Strike, my family to New Philadelphia, Ohio, where another new wire and nail mill was put in operation. I was still too young to work in the mill but made almost daily trips there to take my dad his lunch. I can recall that the superintendent of the wire mill was having a lot of trouble with production due to the fact that the wire drawers wouldn’t work steadily. They’d report for work in the morning, but about ten o’clock they’d knock off and walk a mile to the nearest saloon for a glass of beer. It was an established fact at that time that wire drawers to have beer on account of the lime dust.

Finally. in desperation the superintendent promised to have beer delivered to the mill each morning and give the boys a drink on the house for each hour they worked. Believe it or not, it worked! That was my first experience with the incentive system.

After a few years in Philadelphia the seasonal slump which early industry and accounted for much of the roving of the old-timers hit again and with still hard, the McGowans moved to Braddock, which is from almost 10 miles to Pittsburgh. With every nickel counting, I had to leave school and take my first job at the Pittsburgh Wire which was later sold to Consolidated, then to American and Wire, and which plant has since been dismantled.

When I went there it was a new mill and I worked for my dad on the packing floor. When I was promoted to weigher at seven and a half cents an hour, I was a happy kid. Later I was able to get a job as a nail machine helper at ten cents an hour. Here I learned my trade and became a full-fledged machine operator, proud of the fact that I was the youngest operator in that mill. My job adjoined the wire mill on one side and the annealing pots on the other side, so in my spare time, I learned a bit about wire drawing and annealing.

At that time the Braddock mill was considered a very modern operation. It produced 500 tons of wire and specialized in wire for nails and barbed wire. The baker was coal-fired from underneath and requited a fireman on each turn who in addition to firing had wheeled his coal and ashes. There were two cleaning circles and a smaller one for copper coat and soft wire.

There were several annealing outfits, and these were loaded while cold, the pot sealed with fire clay and a fire built under them. Timing and temperature were guesswork. When the fire was to die out slowly, the wire remained in the pot until the pot cooled. This required a couple of days. The battery of the pot was handled by a steam-driven crane that traveled on a track parallel with the pots.

All of the wire drawing machinery was old-style single-drawn benches driven by steam engines. A drawer who drew four to five tons in ten hours was considered a good tonnage man. In those days a wire drawer had to have considerably more experience than a like man today. All first-class wire drawers were also what is known as plate setters. The wire was drawn through a set of the plate each with 12 to 18 tapered holes in it. These plates had to be battered hot which was usually done by the drawer and his apprentice at the end of their turn.

They came in early the next morning and set the plates before going to work. There was no question of time and a half in days as it was all tonnage, A young fellow started by helping an older wire drawer and his first job was redrawing on what was known as the fine bench. As he grew more experienced, he was promoted to the rod bench and he was then on his own.

Among the men who will be familiar to you who were at Braddock in those days was a young chap Nullmeyer who was interested in the engineering department. James Farrell was in the sales department and later was works manager before going on to make history in the steel industry. His brother, Bill was superintendent of the wire mill.

In 1899, I moved on to a little mill down the Ohio River called the Ohio River Nail Company and after one year at this plant, I moved to Ironton, Ohio, where the Belfont Iron Works, an old-time company that made iron cut nails, had decided to go into the wire nail. During a shutdown, you would make a living any way you could. I know that I have put in many hard licks in off-season months working in a hotel, in a summer amusement park, with a construction gang, and other odd jobs that came my way.

I recall that once when the mill was down in Ashland, Kentucky, I believe it was John Mordica who made a living as a photographer. So, you see, the early wire mill men had to have other talents than skill at his chosen trade. During one of those shutdowns at Belfont, I went to Kokomo, Indiana to work for the Kokomo Nail and Brad Company, a small concern that purchased their wire and made small brads, cigar box nails. nails and other specials.

After five there, I went back to Ironton and when the next shutdown came, I moved to Peoria where the Keystone Fence Company had just put in a new wire mill, wire galvanizer, eight new machines, and one staple machine. I signed up as foreman of the nail mill, combined with the duties of timekeeper, packing boss, toolmaker, knife grinder, and stable maker. I supervised the installation of the nail machines and shortly after we got the mill in operation, the nail operator, who was supposed to do everything I didn’t do went on a protracted drunk and I needed up by being the whole nail department.

The mill at Ironton was also closed but while I was there, I was told that there was a labor agent in town seeking skilled nail makers to go to Ensley, Alabama. In those days it was standard practice for mills to employ labor agents who toured the country rounding up workers.

I mention this incident to give you an idea of the poorer type of employee relations that existed in the early days. These labor agents painted glowing pictures. They promised such things as rail fare, high wages, etc. In my case, I was offered transportation to Alabama, 30 cents an hour, which was high then, and work in a brand-new mill.

When I arrived at Ensley, what a different story! First of all, the rail fare came out of the first month’s check. We were paid only once a month, but the company generously offered advances to any who needed them, and it wasn’t until later that you learned that the advances bore interest at ten percent. I quit after three months and went to Atlanta where the mill had been in operation for just three months. [this story goes on to talk about Atlanta’s mill]

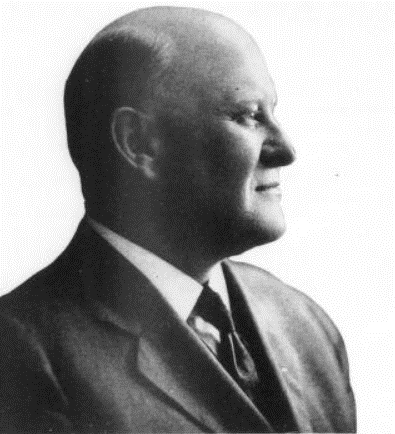

In Memory of John Mordica 1873-1937

0 Comments