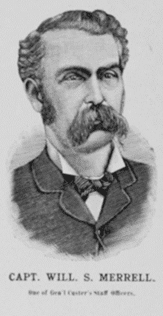

Ironton Register 10 May 1888 – The Register man got after W. S. Merrill, this week, for a “Narrow Escape.” He said he thought it a very “Narrow Escape” for anyone, to serve through the war and live to get home, taking into consideration the hardships, privations, &c., that a soldier had to endure, in four years and a half of active service.

W. S. Merrill enlisted as a drummer boy in the first company raised in Lawrence County, in April 1861 and worked his way up through all the grades to Captain, serving until the close of the war in 1865. In the course of a long talk Capt. Merrill said substantially:

“I had several ‘Narrow Escapes’ but will give you one which I think will always be most forcibly impressed on my mind. At the time it occurred, May 20, 1863, I was Sgt. in Company K 2nd West Virginia Cavalry. Companies G and K were camped at Fayetteville and attached to Col. White’s Brigade, composed of the 12th, 28th, and 37th O.V.I. Our principal duty was scouting and standing picket.”

W. S. Merrill continued, “At this time, Gen. Scammon was in command in the Kanawha Valley, with headquarters at Charleston. He was in the habit about two or three times a week, telegraphing orders to send the cavalry in nighttime out through the mountains to look for the enemy and see if he was advancing.

One of these famous orders came on the night of May 19, 1863, ordering the cavalry to proceed toward Raleigh Courthouse, find the enemy’s pickets, charge them into their camp and find out the number of the rebel force, how much artillery they had, &c.

“About ten o’clock at night, about sixty of Company K and G, under Capt. Morgan left the camp under the above order. It was so dark that if Lee’s whole army had been within fifteen feet of the pike, we could not have seen them, but on we went until, about the break of day, we saw a cavalry picket on a hill about fourteen miles from our camp.

The captain told us not to fire, but as soon as they fired, to charge them into camp, which we did, reaching there as soon as they did, and the rebs were all asleep in their tents. We woke them up, you better believe, for a few minutes but we did not stay long, for there were about 3,500 of them and 12 pieces of artillery.

“Well, we gave them a bad scare but when we got in among so many, we were scared about as bad as they were. We moved rather briskly back toward camp with about 200 cavalries following. The captain took advantage of all good positions and warmed them up occasionally.

When about eight miles from camp, near McCoy’s Bridge, we got a good position and were going to give them a few rounds when to our surprise we were fired into from the rear by rebel Infantry who was on the pike near the bridge,” said Merrill.

“The captain ordered me to take twenty men and charge through them and try and get to the Infantry outpost, which was a little over a mile off, where there were two Companies. It looked rather bad for us, but we drew our sabers and down the pike we went into them, chopping right and left and driving them pell-mell onto the bridge before they hardly knew we were coming.

When we struck the bridge, the first section between the abutment and the pier gave way, and away we went, rebels and cavalry all in a heap, about fifteen feet into the creek below. I was sensible until I felt my horse strike the ground when I lost all consciousness.

“When I came to my senses I was fast in among the men and horses who were killed and crippled, and our forces were on the hill on one side of the bridge and the rebs on the other, fighting to get possession of the bridge. (As I afterward learned, the two Companies of Infantry came on the scene from the picket post about the time we went through the bridge).

It took me some time to get out, which I managed to do by leaving one of my boots under my horse and crawling down the creek and out into the laurel, for I was hurt so badly I could go no further. The firing at the bridge lasted some time when the rebs opened up with a piece of artillery when our men retired.

“Well now, I tell you, as I lay there, I just about made up my mind [that] my time had come. I was wounded in the left hip, a cut on my head, three ribs fractured near the spine, mashed, bruised all over, and right there within 200 feet of the rebels, who were now at the bridge working away to repair it, and some robbing the men and horses who were laying under it of everything of value.

I saw the command we had chased into their camp that morning cross the bridge after it was repaired, and move on toward our camp, and in about two hours heard the fight open near Fayetteville.

“I now made up my mind to try and reach camp, but I was on the wrong side of the pike, and I had to wait till near evening before I could venture to cross, an account of the stragglers. I was just about to start when I heard footsteps near. I thought now I am good for Libby or Andersonville, but it turned out to be Lieut. –, out of the company -, whose name I will not mention for reasons I will give further on. But I was very glad to see him.

He said his horse had been killed in the fight, and he had to take to the laurel to prevent capture. I crawled over the pike safe, taking the direction of Cotton Mountain. Having given out early in the night, we lay down till daybreak, when we started again, but it was very slow traveling with me, I tell you, and the third day I felt like I could go no further.

But we reached the foot of the mountain and came near being captured by rebel cavalry. By this time, my hands and knees were so sore I could hardly crawl. I cut two forked sticks for crutches, but they wore all the skin off my arms, so they were thrown away and I crawled on up the mountain.

“When we reached the top, we came to a log house furnished and a fire in it, but no one about. I was now about starved, it being four days and four nights since I had a bite except for sassafras buds, and bark. I concluded to stay by that house till someone came and get something to eat.

But we heard someone call up the ridge. I crawled up there and looked around, and there at the foot of a large tree, not fifty steps away, sat five men with butternut clothes on. I was sure we were lost at last, but I could see no arms on them, and I told my friend John – we would not let them take us, if they were not armed, as we each had a navy revolver.

I asked them who they were, and they said, ‘friends, come down.’ I went to them, and they proved to be loyal men, hiding out from the rebels to keep from being conscripted. I looked around for John – there he stood, poor fellow, on the ridge with a letter fastened on his cane holding it up for a flag of truce. He had surrendered.

“I learned from these men that the rebels were clear around our camp, and I gave two of them $10 a piece to carry me six miles to the Kanawha River, where I came across Capt. Alex Ricker, of our regiment, in charge of a train, kindly sent me in his ambulance to the regimental hospital at Camp Piatt.

I expect I have about worn out your patience with this escape, but as I was four days and five nights escaping it takes considerable time to tell it. Call again when you want another.” This ended W. S. Merrill’s story.

The Jackson Standard, Jackson, Ohio, 21 Oct. 1875 – W. S. Merrill, of Ironton, formerly Sheriff of Lawrence County, was terribly stabbed and cut in a drunken row last week. It is thought he will die, as his bowels were severed in one place.

0 Comments