Col. W. H. Raynor Interesting War Experiences

Narrow Escape #50

Ironton Register – 27 Oct. 1887

Submitted by Martha J. Martin

At the generous supper table of Dr. Ewing, of Jackson, we were introduced to Col. W. H. Raynor, of the old 56th Ohio. He is a large man, of robust health, clear eye, fresh complexion, and very companionable, though somewhat modest in his demeanor.

He enjoys the peculiar distinction of having met with a very singular, “Narrow Escape” and having it told, at great length, by a distinguished author, John S. C. Abbott, in Harper’s Magazine, twenty years ago.

We read it at the time, but the facts had nearly faded from our memory, and would sometimes go entirely, had we not met the hero himself, and enjoyed the story from his own lips.

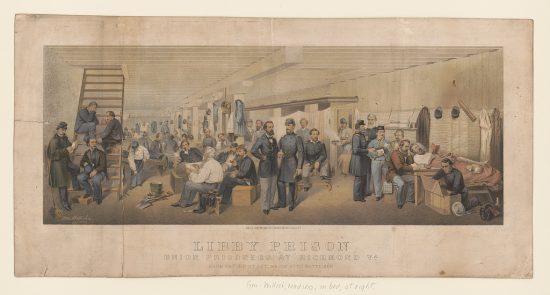

It happened to be mentioned at the table, that Col. W. H. Raynor had been in Libby prison, and the ladies were quick to ask him more about it, and for them, he told the story. The Colonel is now a manufacturer in Toledo, Ohio, a very practical man, and so he did not garnish his narrative with any startling effects or rhetorical streamers.

“He was made a prisoner in the early part of the war, at the time of the Vienna Ambuscade, or shortly after. That was the first time he was a prisoner. He was then a Lieutenant in the three months’ service.

He afterward became Colonel of the 56th Ohio and was captured while running the rebel batteries on Red River in 1864. He was wounded both times he was captured. But it was during his first capture, and while a prisoner at Libby Prison that his exciting narrow escape occurred.

“It happened in this way. ‘There were several wounded union soldiers at Libby, at the time, and the services of the rebel surgeons being demanded elsewhere, the care of these union soldiers were turned over to the union surgeons who were in prison.

At first, the regulations were strict, but after a while, it was found very inconvenient to give a pass to the union surgeons every time they wanted to go out to get a little medicine or something that was needed for the sick and wounded, so they provided the union doctors with a red rosette and let them out on parole, that parole providing that their liberty should be used solely for the needs of the sick and wounded and that they would promptly return to prison, whenever allowed to pass the guards.

So that little red rosette was regarded as a sign of freedom and they who wore it, went in and out of the prison, and through the streets of Richmond unmolested.

“Of course, this regulation suggested a very important question to the other prisoners – why not get rosettes too, and go forth and keep going, and get back to God’s country again? This subject impressed itself on Col. W. H. Raynor’s mind, and he and three other prisoners resolved to play the surgeon and get out of there.

But how to get the rosettes was a great difficulty. Of course, it would not do to sound the surgeons about it, or borrow one of their rosettes, or get them to procure some suitable material for the surgeons were on their honor and must not be approached. Col. W. H. Raynor says he tried every way to get someone to buy him some red ribbon at a Richmond store but failed.

At one time, he made an express contract with a fellow who came around to sell pies and trinkets to the prisoners, but the fellow never came with the ribbon. For a long time, they worked to get the material to make rosettes of but were disappointed. At last, after nearly giving up all hope, Col. Raynor says he observed a red shirt hanging up, drying in the prison.

It belonged to one of the prisoners. Immediately, the thought struck him, why not make rosettes from that red shirt? He forthwith set about to do it. Cutting a few strips from the shirt, he retired to his corner, apprised his three associates, and soon four rosettes were the result.

“Now, came the dangerous part of the program, the going forth past the guards, and out into Richmond, and beyond. So, the time was set, and Col. W. H. Raynor was to try it first. He boldly walked down to the door, where the sentinel stood holding a musket, with the bayonet resting against the opposite side of the door.

Raynor simply lifted the gun up and passed as if he had done it often before. The sentinel saw the red rosette and let him go on. Once out in the street, it didn’t make much difference whether he wore the red rosette or not, as his clothes were as gray and ragged as those of any reb. He sauntered through the streets unmolested. He met crowds of people, but no one questioned his liberty. But he got into a bad fix at one time.

“A reb. soldier, who was a little tight, accosted him, and with a slap on the back, asked, “what regiment do you belong to?” The Colonel was fortunate enough to know that the 30th Virginia, was at that time, forming there, and so he answered, “the 30th Virginia sir,” whereupon the man retorted, “so do I, by –, let’s go in and take a drink.” They were in front of a saloon, and quite a crowd surging about, so apparently intent on accepting the reb’s invitation, gave him the slip and disappeared.

“He forthwith took his bearings and struck out for the Potomac, which he reached without any particular mishap, except that he had to constantly sneak his way through, traveling at night and through the woods. He finally arrived at the Potomac where he soon found a union gunboat and was safe. His three companions also made the trip successfully, one of them being Col. Hurd, well known by many of the old citizens of this region.”

0 Comments