Reminiscences of Richmond During the Civil War was published on Dec. 21, 1899, and was abstracted by Peggy A. Wells for The Lawrence Register website.

Southern people do not become reminiscent very easily, and regarding civil war history, there is scarcely anything said except that they had a very hard time.

On some occasions, a leading question will bring out a complete acknowledgment. As memory traces the old deficiencies, you will see a shadow creep over the face, and a hearty “Thank God, the war is over” will burst out unwittingly from the heart.

We have never known the sad, dark days that surrounded the Christmas of 1864 in Richmond, and I pray to God that never more in history will come such a time of suffering and distress.

Flour was from $500 to $800 a barrel. Men were $10 to $20 a pound and very scarce at that, but articles of clothing and shoes were at fabulous prices, and one man told me that he had paid $7,000 for a suit of clothing, including a hat and shoes.

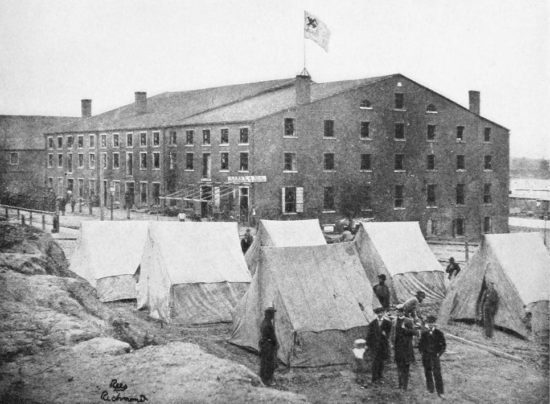

Large numbers of Union prisoners were in Libby. A great many southern Union men were in Castle Thunder over on Belle Island: and the saying often answers the fact that these men were not well fed, “They all got as much as we did,” looking at the situation now, it is a wonder that they were fed at all.

Very common meals at the famous hotels were sold at $10 and $50, and every private home practiced the strictest economy in all kinds of supplies. Seventy-five dollars was paid for a tough old hen and another $75 for the bread and cooking necessary to make dinner for three officers who spent Christmas in Richmond. Nearly $100 more was needed to pay for the liquor used, which was only homemade “corn juice.”

There were wounded soldiers in nearly every house and thousands of sick and wounded in the hospitals, so the ladies who had any Christmas fixings sent them to these suffering brothers. Toys were not attempted, and the children were told that the Yankees had captured old Santa Claus, and several letters were sent to them urging that he be made free at once as a non-combatant. They looked for him, but he did not come, and no wonder that in their hearts, they did not love the northern bluecoats that kept away their last friend.

There were many people in town under British protection and a large number of Welsh ironworkers who made iron for the government but who would not fight nor drill only as city guards, and every one of them was known as an enemy and watched accordingly so that they were prisoners while the war lasted. Several of these mill men had struck for a larger allowance of meat and always made the rulers yield, as their work was badly needed.

We said to one of these: “How did you fare on holidays and Sundays?” “Oh,” he said, “it was always the same, and toward the last, there were no holidays or Sundays, but work every day, and the food was not fit for a workingman.” “Did you hear the guns sometimes?”

“Oh, yes, and we knew they were coming closer, and soon we would see the wagons bringing in the wounded, and while every fight was a ‘victory’ to us, we noticed the next time the cannon roared, it seemed still closer. Oh, yes, we did have a bit of Christmas then. My old woman did make a plum pudding, and we had a goose cooked for dinner, and Mr. Edwards, Mr. Jones, and David Davis came over to our house with their families.

About the time for dinner, they said a Yankee raid was coming to destroy the works, so my wife hid the goose and the pudding, and we waited till the next Sunday, and we had a feast, anyhow. “Many of these Welsh people and their descendants are now wealthy, and those who work at the mills today are later immigrants who have settled here.

As I look out my window, I see where Libby stood, and over in the river is Belle Island, where Castle Thunder held so many aching, lonesome hearts on that dark Christmas day in 1864, where General Powell had been thrust with nearly a fatal wound a year or two before, and where Captain McCabe sang his “Glory, Hallelujah,” while they lived on small rations, and where John N. Stewart, of Haverhill, Ohio, looked through prison bars for years and finally died a prisoner, and is now sleeping in an unknown grave just beyond Chimborazo Park.

That Christmas day, a feast of love and tokens saw a people divided, struggling, bleeding, and dying; but the love has triumphed, and a new Christmas feast appears where all is peace and prosperity.

The bells ring; the people fill the churches; happy hearts praise God; the people have forgotten; the angel’s song of “Glory to God in the highest, peace and goodwill to men” can now be heard in the roar of the train and the rattle of the factories.

PILGRIM

0 Comments