Cincinnati Commercial 17 Jan. 1870

A lot at one of the Ironton furnaces on the bank of the river here will not convey a just idea of furnace life. To see that in its native purity, one must take the Iron Railroad and run out to the furnace region. Here you find a very broken, hilly country, extending out the entire length of the road. All the heavy timber has disappeared, and a scrubby second growth succeeds. There are no lowlands, but hollow simply, through which at this season little streams of chalybeate water go brawling toward Ohio.

The hills all have a singed appearance – not merely the bare appearance of winter-withered verdure, but a blasted and barren dreariness, such as invading armies leave in their wake. At a certain altitude upon all the hillsides around appears a little ridge like a country road.

That is the ore seam followed around and peeled off for the past twenty years. Some of the hills, especially those immediately back of the city, are tunneled or “drifted” for coal, the same quality procured at Pomeroy. Six thousand bushels per day are taken out for consumption by the manufacturers of Ironton, and the drifts promise an exhaustless supply. Pity, it will not answer the purpose of the timer in the manufacture of “pig.”

There is, however, an experiment being tried at Lawrence Furnace, ten miles out from Ironton, with Ohio coal. This furnace has exhausted its timber, as several others have, and the transportation of charcoal from a distance became so expensive and uncertain as a purchasable commodity, that Lawrence was remodeled for a “hot blast” stone coal furnace. The furnace costs its owner, John Peters, $150,000. If he succeeds in making Ohio coal answer the same purpose as the Coalton coal used at the Ashland, Kentucky, furnace, his fortune is made; if he fails, he loses his investment, and his example will deter others.

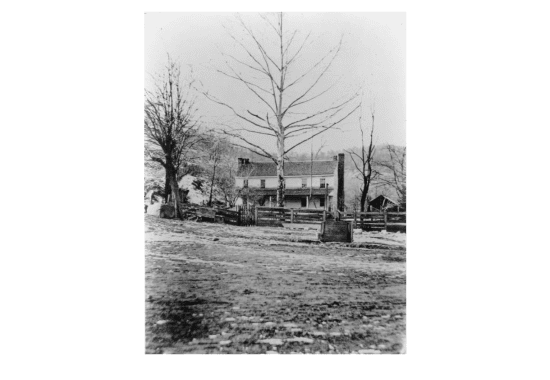

The furnaces are situated here and there among these auriferous hills and present the same general appearance. The life aspect is the same about all – not inviting. It is not, however, to be judged by appearances merely. As a general thing, each furnace has scattered around it among the hollows, a number of log cabins, each provided with a good stone smoke stack and a fenced-in plot of half an acre or more of ground for a vegetable garden. These are owned by the furnace company and are given, rent-free, to the workmen.

The community, averaging two hundred and fifty, perhaps three hundred people, are supplied from a store in which they may purchase or not as they choose, but there is to be found in it everything necessary and comfortable to the laboring class, except the curse of all industrial life, whisky, at an advance of wholesale prices barely sufficient to pay the expenses of transportation and clerk hire.

Any honest furnace laborer will tell you this, and this besides, that he can save money by buying at the store rather than in the city; that he can always get his money when he asks for it and is always able to lay up something for a rainy day.

Furnace laborers and their families use goods only of domestic manufacture; indeed, it is a matter of principle with the pig iron princes to supply no one else, and they are good enough for any people’s wear. Whoever doubts it, made little of the opportunity of the great exposition of textile fabrics, held in Cincinnati last year.

There is an air of native simplicity about the furnace people, that suggests a remote period of existence. Looking at them at work, either on the hillsides peeling the ore, or hauling it with six-yoke ox teams to the furnace, conscious all the time of the stupid stare their timid women and children greet you with from the cabin doors, you half forget that the stared at and the stares, the workers and the wonderer, live in the nineteenth century, with its stupendous achievements by the aids of steam and electricity.

But these people are quite as well aware of these as you; they have a school, a church, a place to vote, and all the common means of plain common school education’ a little in the rough, to be sure, but still not inferior to the opportunities of incorporated villages and towns.

The physical health of these diggers and delvers is excellent; the children are ruddy, the women free, at least, from the worn, pallid, pitiful aspect of the poor of cities always present. There are “shirks,” but no beggars, and there are some out-and-out rascals. Along comes a fellow looking for work.

He is a miner, or a chopper, or something else, and the first step is to give him a cabin and advance some articles – a blanket, pick, shovel, groceries. He works awhile, not long enough by half to pay for what he got, and then “takes a new department;” goes, in fact, to the next furnace, and repeats the same program, until he has gone the entire rounds of the furnace region.

Then he “plays out.” The fellow loves whiskey, and it made a rascal of him, as it does of all over whom it gains control. No moralizing now, but a simple statement of facts. Every furnace loses more or less every year by bad debts, of which the itinerant rascals make now a few.

Work About the Furnaces

It has been shown that the iron ore crops out of the hillsides. The men who procure it are called “diggers.” A shovel and pick are used in the work. The dirt is shoveled away and the ore is picked out and shoveled into the ox-wagons and hauled down the hillsides to a wide open space near the furnace where it is heaped in alternate layers with brusque, vulgarly called braze-fuel, coal, timber chips, or chopping’s, and the set on fire as a preliminary to throwing it into the furnaces.

This process turns the ore from its light gray color to a reddish brown, and sometimes melts the ore into what is called “looping.” The digger is paid from $3.50 to $4 per run. If he has to “drift” the ore – that is, mine it when the “dig” I deep, he gets $5 per run. The hauling costs from fifty cents to one dollar and a half per run, according to the distance. The teamsters mostly own the teams.

Laborers in the furnace receive $1.50 per day; the skilled laborer is paid as high as $4.50 per day. The foundry man, as the man in charge, of the furnace, is called, is paid $1,200 per year. There need be no idleness about a furnace. Each season has its appropriate work.

An important feature of furnace work is charcoal burning. The timber is chopped in winter and charred between the months of April and November. Charcoal burners are a peculiar class. They live a gypsy sort of life and are migratory. They sow not, and neither do the spin.

The prodigal son, who comes from swine feeding, did not present a more picturesque and forlorn appearance than they do. Begrimed and tattered, they look like scarecrows and do not seem endowed with a capacity for a higher purpose. The miners are employed by a boss, who gets the contract from the furnace and comes out at the end of a season with from $100 to $500 clear gain.

Charcoal is made by chopping the timber in lengths of three or four feet, setting them up on end in pyramids, covering them with leaves and dirt, and setting the piles on fire. The dirt prevents the piles from going off in a blaze, and they smolder away until only the charred timber remains. The burners chop in winter and get from sixty to seventy-five cents per cord. A good chopper will cut two cords of wood per day. The contractor is paid by a load of charcoal (two hundred bushels) and gets from $9 to $10 per load, according to the distance it has to be hauled.

It is represented here that many of the furnace hands are well off; that is, they have from $500 to $1,500 in bonds in the bank, and credits on the furnace company’s books for several hundreds of dollars bearing six percent, interest. You are shown this one and that one working about the furnaces, not differing in appearance from his fellows heaving coal, stacking or piling pig, and told that he owns a house and lot in the city, and is worth in ready money two or three thousand dollars, being added every month he works. He doesn’t drink whiskey.

The conditions of some of the furnaces are better than other; better, at least, in appearance. They furnish frame shanties for their workmen, but your regular out-and-outer, you’re dyed in the wool furnace hand will not hesitate to take a log cabin in preference. It is warmer in winter and cooler in summer, and every way more congenial to him.

Manufacture

The pig is brought in on platform cars over the Iron Railroad that took us out, and it also brings in the coal consumed by the manufacturers in the city.

The Lawrence Iron Works Company comes first in the capital, with $225,000 for the mill alone. It was built in 1853 for the manufacture of merchant bar iron. Its capacity is six hundred tons of finished iron per month on a single “turn,” or ten hours per day.

It has a specialty of hoop iron of all sizes, with a capacity for 250 tons of hoop per month, mostly oil barrel sizes. The regular sales are forty tons per week of these sizes, besides large quantities of buckets and flue hoops. The company owns business houses – one, Nos. 16 and 17 Public Landing, Cincinnati, and the other, No. 113 Main street, Louisville, Kentucky – where all the manufactured iron, except for home trade, is sold. The metal used is that produced here. The workers employ 225, who are paid semi-monthly in cash. The amount paid for labor alone averages $15,00 per month.

The foundry of Woodrow, Mears & Co. manufacturers of hollow ware and castings, with sample rooms at No. 21 East Second street, Cincinnati, you know something about. It is probably the largest stove foundry in Ohio.

The Belfont Iron Works Company manufactures cut and wrought nails and spikes exclusively. They manufacture their own “pig;” and employ two hundred hands at the factory, and a hundred at the furnace.

The “pig” is first broken and pulverized, then melted and rolled into plates three feet long and twelve inches wide. It is cut into strips from seven-eighths of an inch to seven inches long, and the nailer holds one of these in a pair of tongs to a ponderous pair of nippers, which move rapidly like a monster’s jaws.

Each movement snips off piece crossways of the bar, just the thickness of nil, and this drops into the throat of the monster, where a head is “mashed” on a double-sided pressure brought to bear that gives the nail shape. The concern turned out 100,000 kegs of nails and spikes, all sizes, last year. And, now, having taken a particular as well as a general look at Ironton, let us see the moving spirit of the place.

John Campbell

This man was one of the first, perhaps the first, to think about establishing a town at this point. He was born and raised in Brown County and went to school with General Grant. He is of Scotch-Irish descent, in politics an original Abolitionist. He stands over six feet high in his socks, is sixty-three years old, weighs two hundred, and enjoys vigorous health. His features are strong, with a powerful will, indicted by the firm set mouth, prominent chin, and square jaw. His eyes encounter you with a shrewd, searching glance, and your fate is decided there and then.

Mr. Campbell is what is understood here as an Iron man, eminently practical, exceedingly simple and plain in his habits, and therefore caring little for the graces and accomplishments of society. He hears about the same relation to them that “pig” does to pocketknives. He is rich, but no one calls him to mean, and that is eulogy enough.

Mr. Campbell’s zeal during the war for the Union commended him highly at Washington, and if inclined to public life he might have had enviable positions, but he stuck to his “pig,” and comes out a richer if not a more honored man in the end.

Mr. Campbell is to Iron what Mr. Horton is to Pomeroy, a public necessity. His energy, influence, and wisdom are felt in every department of the industrial life of the place, and nothing of a general character is undertaken without him being consulted directly or indirectly. He has sustained great losses mainly through the failure of others, but all his transactions are characterized by foresight and crowned with success.

E.B.

Furnaces Run on Christian Principles More Productive than Others – The Rich Men of the Hanging Rock District – List of Furnaces in and out of Blast

Hanging Rock, Lawrence County, Ohio 13 Jan. 1870

In old times, which means before Ironton was thought of, steamboats landed at this picturesque place on the Ohio River four miles below, and when the iron manufactured in the region found its way into the market, it was called Hanging Rock iron to distinguish it from all other kinds.

Situated pretty much as Pomeroy is, on the narrow strip of level ground intervening between the river and the high rocks only gunshot distance from the decks of passing steamers, Hanging Rock differs from it only in general appearance by being smaller. A projecting mass of rock high up in the natural wall, threatening to crush all beneath, gives names to the place.

The township is called Hamilton, in honor of one of the founders of the place, Robert Hamilton, Sr., deceased, who came here in 1828, and is between six and seven miles long on the fiver, and a half mile wide and contains a population of over eight hundred. A railroad, with a tunnel 610 feet, built by Mr. Hamilton, runs out three and a half miles to the coal banks, and the purpose is to carry it two miles further, to reach Pine Grove Furnace. The coal “drifted” here is the same quality found in the Pomeroy beds. A million and a half bushels are taken out annually.

Thomas W. Means, the richest pig ironist in the region, resides here. He came from South Carolina to Adams County prior to 1820 and was among the first to develop the iron resources of the region. He owns the Pine Grove and Ohio Furnaces reached by Hanging Rock, and the coal beds in the locality, and has an interest in the Buena Vista, Belfont, and Amanda furnaces in Kentucky; and in the coal beds and railroad at Ashland, Kentucky.

The distinguishing local feature at Hanging Rock is the place of Captain S. B. Hempstead, a wealthy and retired pig-ironist, who has expanded largely in cultivating the element of beauty and enjoys a wide reputation and deserved popularity. After Robert Hamilton, he was the first furnace proprietor to break up the combination of furnace men to work on Sunday. It is still claimed by many of them that furnace work can not be suspended on Sunday without a positive loss. Captain Hempstead proved the very contrary to be the fact, namely, that working a furnace unceasingly was attended by loss.

His predecessor, Mr. Hamilton, made the innovation and was bitterly opposed by operatives as well as proprietors, but he persevered and won the day. He commenced fist at Pine Grove, simply out of respect for the Sabbath, and was ridiculed and execrated for his pains. His compeers undertook to argue the case and asserted that he simply lost a seventh of the iron the furnace could make by stopping, but he cared nothing for that, he said, and would lose all rather than desecrate the Sabbath.

Difficulties were next thrown in the way by the workmen; they would manage to give the furnace a backseat in some way out of sheer spite, but all these were conquered in due time, and the day of rest was, and is now, regularly observed. Captain Hempstead maintains that every furnace can be stopped on Sunday without any more inconveniences or detriment than rolling mills, foundries, &c. are stopped.

All that is lost is simply what is not made on the Sundays of the year. When Ohio Furnace fell into Captain Hempstead’s hands, he had it stopped on Sundays, in keeping with Pine Grove, and when he disposed of his interest in the furnaces to Means, Kyle & Co., in 1864, the system was maintained.

These furnaces produced a larger average than any others in the Hanging Rock District, and it is claimed that I was owned to the superior system and management that a day of rest in the seven produced. The following exhibit is interesting after it is stated that the average production of furnaces is thirteen tuns per day.

- Pine Grove averaged fourteen tons of iron per day in 1867 but did not do full duty.

- In 1869, Ohio Furnace produced 3,152 tons in 214- and one-half days.

- Pine Grove Furnace 3,406 tons in 214 21-24 days.

- Ohio averages 14 72-100 tons per day.

These furnaces are in reality the only ones in the region that stop, “square off,” work on Sunday.

The observance of Sunday is found to attract a better class of men to the furnaces, men who do not stoop to the debasing influence of drink, and who take a more active interest in the education and proper bringing up of their children.

There are six hundred men employed at Pine Grove Furnaces and the coal drifts, nearly all Germans, who live in neatly constructed log cabins, which are kept white-washed and cleanly as any country house. Each cabin has its little patch of the kitchen garden, and the furnace community lives in perfect harmony and contentment. They have day and Sunday schools, regular worship, and holiday frolics. This is mentioned that the fact may not slip your mental grasp, dear reader, that these furnace people from a community separate and distinct; that they live out of the ordinary lines of travel, and in short, live a life peculiarly and altogether their own.

The pig iron princes live in the towns and cities, in fine, large residences, with spacious grounds, ornamented — may direct and wealth accomplish.

They live on the fat of the land, travel, send their families to Europe, speculate, and sometimes, “burst up,” in which case everybody suffers, from the experts on a yearly salary to the mud-dabbled teamster belching “gee,” or “wow” from stentorian lungs at that six-yoke ox team slowly but steadily winding down the steep acclivity, yonder, you would hesitate to descend without the aid of a stick.

When the “burst up” takes place, the plethoric prince of “pig” suffers intensely. Some pity, some sympathize, some condemn and some help him, but who cares for the teamster? His timid, untidy wife and faraway children, to be sure, and they are all.

Lawrence County proudly points to T.W. Means, for it knows that name signed to a bank check means a cool million: to John Campbell, worth $500,000; John Elliston, $250,00; Cyrus Ellison $200,000; William D. Kelley $200,000; S.B. Hempstead $200,000; John Peters $300,000; G. Willard, E.M. and F. Norton $100,000 each.

They are the specimen bricks with which the wealth of the county is built – a rough, substantial structure, but by and by to give place to something more handsome and attractive. The wealth originated with these, but — their sorrowing children shed the last tears upon their graves, they will build such monuments in elegant residences, and mourn for them throughout the great –ways of European travel, scattering handful of gold as native offerings, by the way, that really must be consoling for the venerable gold bricks to contemplate the succession and something of an inducement for them to drop off as soon as possible and not make any unnecessary bother about it.

Correct List of Furnaces

The following list of furnaces, in the blast and discontinued, or “blown out,” as it is termed, with their locality, is prepared for reference. They are all embraced in the Hanging Rock district:

List of blast furnaces, with headquarters at Ironton:

- Belfont, bituminous coal, Ironton

- Grant, charcoal, Ironton

- Monitor, charcoal, Lawrence County

- Hecla, charcoal, Lawrence County

- Etna, charcoal, Lawrence County

- Vesuvius, charcoal, Lawrence County

- Mount Vernon, charcoal, Lawrence County

- Buckhorn, charcoal, Lawrence County

- Howard, charcoal, Scioto County.

- Olive, charcoal, Lawrence County

Twelve charcoal and one bituminous coal.

Furnaces with headquarters at Hanging Rock:

- Pine Grove, charcoal, Lawrence County

- Ohio, charcoal, Scioto County

- Empire, charcoal, with headquarters in Scioto County.

List of blast furnaces on the line of the Scioto and Hocking Valley Railroad, now called the Portsmouth Branch of the Marietta and Cincinnati Railroad

- Pioneer, charcoal, Lawrence County

- Harrison, charcoal, Scioto County

- Bloom, charcoal, Scioto County

- Washington, charcoal, Lawrence County

- Gallia, charcoal, Gallia County

- Jackson, charcoal, Jackson County

- Morrow, charcoal, Jackson County

- Cambria, charcoal, Jackson County

- Jefferson, charcoal, Jackson County

- Madison, charcoal, Jackson County

- Limestone, charcoal, Jackson County

- Keystone, charcoal, Jackson County

- Latrobe, charcoal, Jackson County

- Buckeye, charcoal, Jackson County

- Lincoln, charcoal, Jackson County

- Hamden, charcoal, Vinton County

- Orange, bituminous coal, Jackson County

- Star, bituminous coal, Jackson County

- Fulton, bituminous coal, Jackson County

Seventeen charcoal and three bituminous coal.

Furnaces near the line of Hocking Valley Railroad:

- Logan, charcoal, Hocking County

- Union, charcoal, Hocking County

Furnaces in Kentucky, opposite Lawrence and Scioto Counties, Ohio:

- Ashland, bituminous coal

- Star, bituminous

- Belfonte, charcoal

- Buena Vista, charcoal

- Buffalo, charcoal

- Hunnewell, charcoal

- Pennsylvania, charcoal

- Laurel, charcoal

- Racoon, charcoal

- Mount Savage, charcoal

- Boone, charcoal

- Kenton, charcoal

Two bituminous coal, ten charcoal.

Furnaces that have been discontinued in the Hanging Rock Iron region in Ohio and Kentucky:

- LaGrange, Lawrence County, Ohio

- Oak Ridge, Lawrence County, Ohio

- Union, Lawrence County, Ohio

- Franklin, Scioto County, Ohio

- Junior, Scioto County, Ohio

- Diamond, Jackson County, Ohio

- Amanda, Kentucky

- Caroline, Kentucky

- Clinton, Kentucky

- New Hampshire, Kentucky

- Steam, Kentucky

- Sandy, Kentucky

In what is called the Hanging Rock Iron region of Ohio and Kentucky, there are fifty-five furnaces in the blast, (12 discontinued, making 67 in all) of which there are:

- In Ohio, 38 charcoal furnaces and 5 bituminous coal furnaces.

- In Kentucky, 10 charcoal and 2 bituminous coal furnaces.

- Discontinued in Ohio, 6

- Discontinued in Kentucky, 6

All the furnaces except the Mammoth at Ashland, Kentucky, the Monitor near Ironton, and the Star and Fulton at Jackson, are built of native sandstone. Those named here, as forming exceptions, are constructed of boiler iron, lined with fire brick. The question of endurance has yet to be decided, as the iron brick-lined furnaces are comparatively new.

E.B.

0 Comments