Jacob Young’s Youth on Frontier

The Herald-Advertiser, September 11, 1938

Although he became a noted preacher, he spent his earlier years in pursuits he later regretted deeply.

Submitted by Lesli Christian

Written by R.C. Hall, Ph. D.

Author’s Note: This sketch traces the career of Rev. Jacob Young for but a few years of his early life and during most of the period during which he showed little signs of ever becoming a minister of the Gospel. But even after he did become a power in the Christian church and a leader of his denomination, he spent most of his time on the frontier and had many thrilling experiences. If you would like to hear more about him in future stories, we shall be delighted to learn of your preference in this matter.

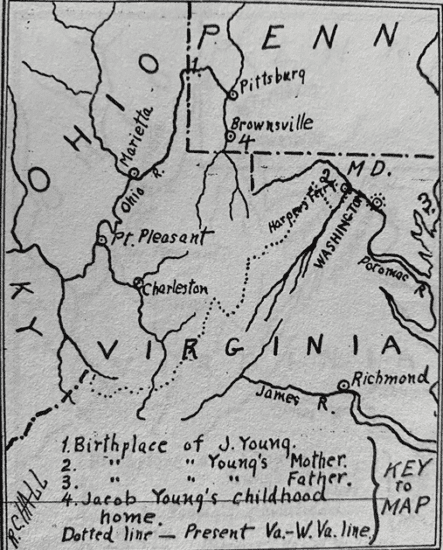

JACOB YOUNG was one of those American pioneers whose biography may be used as a part of the history of any one of several states, for, in truth, he was a citizen of them all. Born in Pennsylvania, of Maryland and West Virginia parentage, trained in the hard school of experience in Kentucky, he went forth to preach the gospel. That great work traveled over many states throughout the eastern portion of the United States.

JACOB YOUNG was one of those American pioneers whose biography may be used as a part of the history of any one of several states, for, in truth, he was a citizen of them all. Born in Pennsylvania, of Maryland and West Virginia parentage, trained in the hard school of experience in Kentucky, he went forth to preach the gospel. That great work traveled over many states throughout the eastern portion of the United States.

Jacob was remarkable in this respect. Blessed with a fine memory and the ability and willingness to relate the experiences of his past life, at about the age of 80 years and with the help of a secretary, he wrote the history of his career as a pioneer Methodist preacher. This work was published under “Autobiography of a Pioneer: or The Nativity Experiences, Travels and Ministerial Labors of Rev. Jacob Young, with Incidents, Observations, and Reflections.”

So, the title page informs us. After quoting “The Love of Christ doth me constrain To Seek the wandering souls of men,” the title page contains the added information that the work was published at Cincinnati by I. Stormstedt & A. Poe for the Methodist Episcopal Church at the Western Book Concern, corner of Main and Eighth streets. R. P. Thompson, Printer, 1857.”

All Name Implies

This book is all its name implies and much more. It not only details the experiences in the life of Mr. Young but presents a vivid picture, or instead, a series of vivid images of the life and conditions of the frontier. Moreover, although he became a recognized leader in his denomination, he never became a high-ranking permanent official. Instead, he remained through his long life, a pioneer clergyman, never out of touch with the ordinary people whom he served so long and so faithfully. Therefore, his story gives a better picture of real life among the people, perhaps that could have been given by a bishop, a college president, or a long-retired worker out of touch with the people about whom he was writing.

Jacob Young was born the very year in which the United States became a nation and penned his narrative some 80 years later. Thus, his autobiography is pretty much a history of the United States during the first eight decades of its existence – but how different from the ordinary school history and almost all other histories, for that matter. In place of telling the story from the outside, so to speak, as a radio announcer describes a ball game, Jacob Young tells his story from the inside, from the viewpoint of one of the players.

A Rare Volume

The reader of this old-time sketch can follow, in imagination, the lives of a pioneer family on the very edge of the frontier during the Indian Wars, its subsequent journey down long Ohio to the backwoods country of Kentucky, its contact with Indians and outlaws, the influence of Christianity in the wilderness and how people lived under what today would by most people be considered intolerable conditions. But this is not intended as a book review.

We merely wish to call attention to this old volume from which we hope, from time to time, to draw information that will prove interesting, thrilling, and enlightening to our readers. Although no doubt there are other copies of this work to be found here and there, we have not yet heard of one other than our own in our community. And since another 80 years have passed since Rev. Young’s work was published, it has probably become a relatively rare book. Moreover, the appearance and makeup are not such as to attract the average young reader of today so that if such a one were to see a copy, he or she would likely pass it up as rather dull reading, which is far from being for anyone interested in the early history of our country.

And so we would like, at this time, to relate the story of the first few years of the life of Jacob Young, securing many of the facts from his narrative and relating them to other facts and other accounts in such a way as to present as accurate a picture as possible of actual life among the people on the frontier about 150 years ago. And in this instance, we mean the frontier of Pennsylvania, Virginia, or that part of it now West Virginia, especially Kentucky.

Born in Pennsylvania

Jacob Young History

Jacob Young was born March 19, 1775, and thus began life a little over four months before the United States of America came into existence. The site of his birthplace was in what later became Alleghany County, Pennsylvania.

His parents, however, had migrated to that spot from Berkeley County, Virginia, which is, of course, today Berkeley County, West Virginia. His father was a native of Anne Arundel County, Maryland; his mother of Berkeley County, Virginia.

They were married in 1769 and settled on what was known as Back Creek in the latter county, but they later migrated to Pennsylvania. Meanwhile, their family had been increased by the birth of two sons named Samuel and Benjamin.

The spot they chose for a home in Pennsylvania was somewhat challenging to locate with exactness since there was no town there, and their house was erected in the wilderness, where they remained for a short time. In his autobiography, Jacob Young merely says in this respect: “They migrated to the western country, at that time called the backwoods, and settled near the Ohio River, about 20 miles below Pittsburg – not far from where Adam Poe had his famous conflict with the Indian chief called Big Foot.”

Now, as far as the incident just mentioned occurred near the present Pennsylvania-Ohio boundary line, according to some of the best historians of that period, and as the affair led, apparently, into what is now Columbiana County, Ohio, it appears probable that the site of the Young home in the wilderness was very near the present boundary line between Pennsylvania and Ohio.

Indians on Warpath

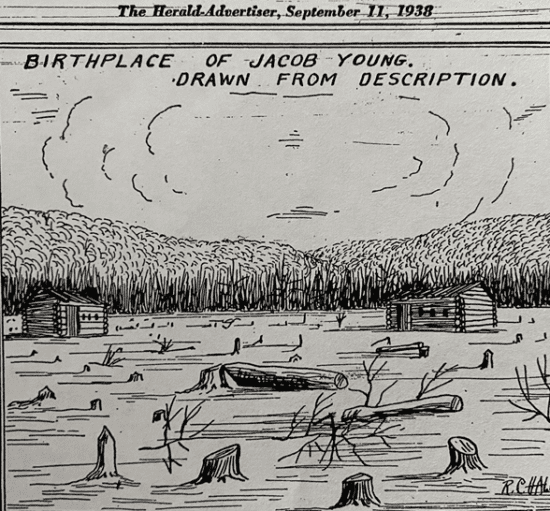

While the exact location of this spot may not be of great importance, it is of special interest to those interested in this particular story because it was there that the subject of this sketch was born. Of the circumstances, or more accurately perhaps, the surroundings attendant upon his birth and the first few months of his life, Jacob Young himself says:

“Few children ever came into the world surrounded by more perilous circumstances than myself. It will be remembered by all acquainted with the country’s history that at this time, the Indian War was raging with dreadful fury.”

Reference is made here, of course, to the Indian War along the northwestern frontier during the Revolutionary War, of which it was a part. Perhaps the most vivid description of his birthplace that can be given was given by Mr. Young himself, as follows:

“The log cabin where I was born stood right on the frontier. My uncle, Richard Young, built a strong log cabin about 30 yards from my father’s. The Indians could come to our very doors without passing the habitation of any white man. But these houses were remarkably well secure.

The shutters to the doors were made of solid white oak puncheons, made smooth and put together with such skill that it was impossible for the Indians to force them. Between the logs of the cabin were small holes called portholes, through which we could project the muzzles of our guns. The ground was so well cleared between the houses that the Indians could not approach without being discovered, and if they attacked one door, they could be shot at through the port holes of the other.”

A Rugged Individualist

The elder Young, according to his son, was a skilled woodsman and marksman and one of those “rugged individualists” of the frontier who relied upon those attributes both to supply his family with the necessities of life and protect it from all enemies, whether man or beast.

As the baby slept in his rude pioneer cradle, carefully watched by his mother and brothers, his father and uncle cleared the ground to raise enough food to supply the little band in the wilderness for the coming winter. As one of the men worked, the other stood guard with a loaded gun in hand and a dog by his side.

But after about a year of such living, Mrs. Young became so nervous because of the constant danger of Indian attacks that the family removed to a settlement on the Youghiogheny River, near where the town of Connellsville later grew up. After about another year, when Jacob was about three years of age, his father bought a small farm near Laurel Hill, Fayette County, Pennsylvania.

After 80 years, Mr. Young was apparently able to recall a number of facts from the third year of his life. He says that he learned later from his mother that as a mere child he exhibited a remarkable degree of activity and courage. But he recalled the kindness of his parents and brothers, visits of his mother’s relatives who lived near, the faithfulness of a Negro servant who was assigned the task of looking after him, and the beauty of the natural scenery.

Spent Hours in Woods

He began to love to walk through fields with his brothers and spent hours in the woods. His father and mother started to see in him those qualities destined to make him more than a commonly useful citizen, and they began to make great plans for his future. But when he was about four years old, it appeared likely that all these plans would go for naught. Of this, he says:

“I was attacked with a bloody flux which brought me very low. My father sat with me in his lap when I could not turn my head. This year appears like a blank in my life, as I remember scarcely anything of it but the misery I suffered. I slowly recovered. Before I was entirely well, I was attacked with confirmed asthma, which lasted till my fifteenth year. Sometimes, it was almost impossible for me to breathe.

It was attended with a very severe cough, which brought on bleeding at the nose. I often sat for hours when the blood was flowing, and I fully expected I should eventually bleed to death. I recollect hearing my father say that I bled so much at one time that the last bleeding would hardly stain a white pocket handkerchief.”

As inferred from the above, Jacob Young had little chance of getting a formal education. While his brothers attended such schools as the vicinity afforded, he was compelled to remain at home because of his health. But he decided that, as he says, he “would not live and die in ignorance.” His father bought some books for him, and his mother became his instructor. he says that he “studied faithfully under her instruction for many a long day.”

Read New Testament

Jacob Young was brought under the influence of Christianity early on. The second book he read was the New Testament, and it produced so significant an impact upon him that he sometimes went out and wept. He acquired a great love of the Savior and says that he thought had he lived in the days when he was upon earth he would have followed him at the risk of life.

Then when he was about ten years of age, one night he became greatly alarmed, arose, and sat by the fire until a voice appeared to say, “Be of good comfort, your sins are forgiven.” He returned to his bed and was a delighted boy afterward. His health improved, too, and his prospects appeared bright.

Mr. Young, later referring to his improved health, says that he “had been a child of affliction” most of the first 15 years of his life and that his “disease” was confirmed asthma, which was removed by taking tar pills or by the assistance of nature. Unfortunately, his changed spiritual condition did not last as well as his improved physical condition.

Being on the frontier and far from anyone capable of guiding him in religious matters, he soon yielded to temptation. One day, while riding a very fractious horse, he was provoked to the point of profanity. And once having yielded to that temptation, it appears that he almost gave himself up to a life of moral recklessness as well as otherwise.

Ceased To Pray

Not only did he cease praying and reading the Bible and give up his attempt to lead a Christian life, but he also began frequenting ballrooms and card tables and attempted to find pleasure in one thing after another, nothing satisfying him for long.

About that time, the elder Young decided to migrate with his family to Kentucky, but several things occurred that prevented it from being made before this move could be made. Chief of these were the Harmar and St. Clair expeditions against the Indians of the Northwest.

It will be recalled by those familiar with this portion of history that the disastrous results of these expeditions to the whites rendered the whole frontier along the Ohio River subject to constant terror of Indian attacks. As the Youngs knew what Indian war meant, they were reluctant to venture into Kentucky under the circumstances and, as they had already sold their farm and lost part of its value in Continental money, they were in straightened circumstances so that Jacob had to work hard to help support them.

But finally, Wayne’s victory over the Indians ended their depredations for a time, except for a few outlaw groups, and it was considered safe for emigrants once more to set out for the “west.” The Young family joined with others in their part of the country to form a band of emigrants to Kentucky. Naturally, the Ohio River offered the most significant advantages of travel from Pittsburg to any point along its lower course, and a boat was prepared and loaded with passengers, crew, household goods, etc., at Brownsville, on the Monongahela River, preparatory to the journey westward.

Down-River Journey

When all was ready for the journey, it was found that the flatboat had sunk rather deep in the water, as it contained 32 persons and 15 horses, in addition to a large amount of furniture and other baggage. The party set out in high spirits, however, and the boat drifted down to the head of Ohio and began descending that stream without mishap.

But as it drifted further downstream and deeper into the wilderness that had so recently resounded to the war-whoop, the feeling of confidence that had permeated the company began to melt away and finally disappeared entirely. Yet, although Jacob Young says that “perhaps he was more exposed than any other individual during the whole voyage,” he insists that “there was no real danger.” By this, he means that there was no danger from Indians. As to other perils, let us note what he has to say:

“It fell to my lot mostly to steer the boat. I was often put to my wit’s end, not knowing what to do. The horses prancing and trying to jump out of the boat, the women screaming at the top of their voices, and cowardly men standing on the bow crying to the right and the left, all at the same time, made perfect confusion.”

Mr. Young, years after, related one experience of this kind in the following simple but vivid language: “One gloomy afternoon we came in sight of an island – some yelled to the right, others to the left, and in this confusion, the boat took the wrong side of the island. All were in danger of being lost. The channel being narrow and the water running with great force, the boughs of the trees leaning over brushed our horses, and it was feared they would jump out.

The women, crying aloud and praying for mercy, had a dreadful time. The steersman became very angry and, to his shame, swore horribly. Having thus quieted the whole crew, he got the boat straight by great exertion, and we glided smoothly through and, in a short time, were in the broad river again.”

Besides steering the boat much of the time, the young man Young also furnished much of the fuel needed for cooking, if not for furnishing warmth. He would go ashore in a canoe and gather wood as the flatboat floated downstream. Then, he would row hard for several hours to catch up with it.

And so, after days and days of such toil and excitement, but without any serious mishap, this band of immigrants reached the Kentucky River, into the sheltering mouth of which the boat was steered and a landing made. Jacob’s father set out for London Station, some 30 miles distant, where the Youngs had relatives who had migrated to Kentucky sometime before and now came post haste back with the elder Young to welcome the newcomers.

They took the Young family and some of its light furniture home with them while the other things were later conveyed by water to Drennon’s Lick. As to the condition in Kentucky at that time, so far as customs and morals were concerned, let us hear Jacob Young’s description. He says:

Found People Wicked

“Although I had departed far from the good and right way before I left Pennsylvania, yet these Kentuckians had gone so much farther than anything I had ever known in wickedness that I was horrified at seeing and hearing them. The very sight of them was painfully disgusting. Their costume was a hunting shirt, buckskin pantaloons, a leather belt around their middle, a scabbard, and a big knife fastened to their belt; some of them wore hats and some caps.

Their feet were covered with moccasins made of dressed deer skin. They did not think themselves dressed without their powder horn and shot pouch or the gun and tomahawk. They were ready, then, for all alarms. They knew but little. They could clear the ground, raise corn, kill turkeys, deer, bears, buffalo, and when it became necessary, they understood the art of fighting the Indians as well as any men in the United States.”

Worker’s Rendezvous

Mr. Young, however, does not leave the reader with merely a statement of how his new neighbors impressed him but relate incidents to show that his estimate of them was correct. One of these which had a direct bearing upon the development of the country was the opening of the road from the place where the town of Newcastle was later established to the mouth of the Kentucky River.

The whole region through which this road was to pass was an unbroken wilderness threaded by an Indian trail along which hostile warriors had been in the habit of passing from the Ohio River to attack the interior settlements of Kentucky, where they had so frequently conducted an indiscriminate slaughter of men, women, and children.

Jacob Young’s description of the rendezvous of the workers is interesting. “Pursuant to previous notice,” says he, “I met the company early in the morning, with my ax, three days’ provisions, and my knapsack. Here I found a captain, with about 100 men, all prepared to labor – about as jovial a company as I ever saw, all good-natured and civil.

Had a man been there who had ever read the history of Greece, he would have thought of the Spartans in their palmy days. This was about the last of November 1797. The day was cold and clear. The country through which the company passed was delightful. It was not a flat country, but what Kentuckians called rolling ground. It was quite well stored with lofty timber, and the undergrowth was very pretty. The beautiful cane brakes gave it a peculiar charm. What rendered it most interesting was the great abundance of wild turkey, deer, bear, and other wild animals. The company worked hard all day – were very quiet, and every many obeyed the captain’s orders punctually.”

Such was road building in Kentucky during the closing years of the 18th Century. But the road-building was not all of this enterprise on which Jacob Young was speaking in the above quotation. He goes on to describe the scene at night when the men laid aside their road-building tools. The captain told them that it was going to be cold, and so he directed them on how to cut hickory trees, mix dry wood with the green hickory logs and make huge fires. A nearby stream furnished water, and so the men warmed their victuals, ate their suppers, related stories of adventures in the Indian wars, and sang some, their singing being rather fine under the circumstances.

Free-For-All Fight

But then there followed a scene so characteristic of the time and place, that no one perhaps could relate it so vividly as one of its eyewitnesses. Thus Mr. Young says: “Thus far, I enjoyed myself well, but a change began to take place. They became very rude and raised the war-whoop. Their shrill shrieks made me tremble. They chose two captains – divided the men into two companies and commenced fighting with the firebrands – the log heaps having burned down.

The only law that I can recollect for their government was that no man should throw a brand without fire on it so that they might know how to dodge. They fought for two or three hours in perfect good nature, till brands became scarce, and they began to violate the law. Some were severely wounded, blood began to flow freely, and they were in a fair way of commencing a fight in earnest.

“At this moment, we heard the loud voice of the captain ordering every man to retire to rest. They dropped their weapons of warfare, rekindled the fires, and laid themselves down to sleep. Suffice it to say, we finished our road according to directions and returned home in health and peace.”

Many narratives of life in pioneer Kentucky offer parallel experiences to those related by Jacob Young, but very few of those who witnessed them or participated in them have left such thrilling, vivid, and doubtless accurate word pictures of them. Moreover, his description of the more prosaic side of frontier life is treated in an equally picturesque manner.

Starting Life Anew

The Youngs having purchased some uncleared land in a remote spot in Kentucky and having spent all their cash, had to earn a living from the soil or starve. A log cabin was first erected, and they moved into it on May 11, 1797. The cabin was without a floor, the tall Oak trees came almost to the door, and the surrounding forest resounded at night to the howling of the wolves.

The prospect was gloomy enough, but all the members of the family being then in fine health, food in the shape of the wild game being abundant, the climate delightful, and no one apparently afraid of hard work, they set about with a will to clear some ground and put in a crop of domestic plants. They also bought a milk cow and made sugar in the spring. Years later Mr. Young spoke of the happy life of those days in Kentucky, although he admitted that for a time he appeared to have no religious impression and took up evil associates and sometimes got into difficulties where even his life was endangered.

In spite of the picture of roughness and immorality as well as of irreligion, which Mr. Young paints of pioneer Kentucky, he admits that among the people there “were some noble families, honorable gentlemen, and ladies, trying to bring up their families in the good and right way, but, as I was a sportsman, I had little communication with them.” And therein probably lies the explanation of the fact that although most of his long career was spent as a minister of the Gospel, those few early years of Mr. Young’s life were spent among some of the roughest elements of the region, so that his narrative of them reads like one of the sagas of the frontier.

0 Comments