The Quakers, Mennonites, and Amish

Although Professing Almost the Same Beliefs and Convictions, These Three Sects Are

Only Loosely ‘Related’ To Each Other

By R.C. Hall, Ph. D.

Submitted by Lesli Christian

(The Herald Advertiser, Nov. 6, 1938)

About a year ago, the Macmillan Company of New York published a volume entitled “Children of Light” which, while prepared from a Quaker viewpoint and largely, perhaps, for the inspiration and encouragement of Quakers themselves and related sections, such as Mennonites, is very instructive and interesting to non-Quakers as well, and to all, perhaps, who are interested in the history both of their country and its religious development.

“Children of Light” is a volume of special importance also to those who wish to make a study of the particular sects which it treats from a sort of investigational standpoint. That is, it bears the stamp of greater authority than the ordinary volume written by one individual and which is likely to reflect that individual’s own ideas and interpretations so as to give but a one-sided view of the subject as a whole.

This volume, however, is not the work of one individual but of many. It was edited, it is true, by Howard H. Brinton, according to the information contained on its title page, but its table of contents shows that it contains 15 chapters, each written by a different author. Perhaps we can gain a better idea of just what the work proposes from the following paragraph from the introduction by its own editor:

Early Name For Quakers

“The essays in this book, although they cover a wide range of subjects, are not without inherent unity of a nature suggested by the title of the collection. “Children of the Light” was an early name for the Quakers, and these studies illustrate various ways and means by which the “Inner Light” was followed by its children. The order is approximately chronological, with similar subjects grouped together.”

While Chapter VIII on the Mennonites and Chapter XII on the Quakers of the Old Northwest Territory

[Quaker Bottom – Union Tp. – Quaker Bottom is now a part of Proctorville. Some of the earliest settlers of Quaker Bottom were “In 1796 John Phillips, Jesse Baldwin, and family, members of the Friends from Westfall, North Carolina; Phineas Hunt and his family, all members of the society of Friends except himself (and he soon became a member) moved to the Virginia side of the Ohio River.

In the latter part of the year 1797, Jesse Baldwin, after raising some corn opposite Green Bottom, moved some eighteen miles down Ohio and settled in what is now called Quaker]Bottom, opposite the mouth of Guyandotte river and the present town of that name.-mm]

are particularly interesting to students of Ohio Valley and so-called Midwest history, the whole volume is a real contribution to religious literature in general. No matter in what period or region one wishes to consider these sects, the essays of this volume furnish an excellent foundation for study.

“Children of Light” was prepared and published in honor of Rufus M. Jones on the occasion of his 75th birthday. Mr. Jones is referred to by Mr. Brinton in his introduction to the work as “one who has contributed more widely than any other person now living to knowledge and understanding of the history of the Society of Friends.”

Further on, Mr. Brinton continues, “We who write this book are able to commemorate only one part of Rufus Jones’ many-sided life and scholarship. Our essays are strictly historical. But in honoring Rufus Jones as a historian, we look up to him as more than a historian. His writings in Quaker history glow with a meaning which is of cosmic and ultimate significance.”

Author of 80 Volumes

Although the object of this review is not to give an account of the life of Mr. Jones, it may be well to mention that at the conclusion of the volume “Children of Light,” there is given a list of the books written by Rufus M. Jones from 1889 to 1937, and they number over 80 volumes which do not include a number of articles. These were published by such reputable publishers as the Macmillan Company, The Abington Press, Harper and Brothers, and others. They cover a variety of subjects, mostly dealing with some phases of Quakerism.

To most people unacquainted with the real doctrine of the Friends, or Quakers, they perhaps mean little except a group of peculiar folks who refuse to bear arms, oppose the taking of oaths, talk with “these” and “thous” and dress in plain clothes. Of course, most people who have read anything at all of the histories of the Quakers know that the sect was founded in England by George Fox and that, in America, William Penn was perhaps its greatest representative.

And since it is from Penn’s branch of the sect that most of the present American branches perhaps spring either directly or indirectly, Americans should be particularly interested in what Penn believed, taught, and practiced. Thus the first chapter in “Children of Light,” which is really in the nature of criticism of one of Penn’s chief works, is of special interest. It is a discussion of William Penn’s “The Christian Quaker,” by Herbert G. Wood, and explains how Penn refutes the charges quite common in earlier days that Quakers were not Christians. It also explains the Quaker doctrine of the “Inner Light” “The Light Within” and “Gentile Divinity,” all of which appear to mean in general that some people are guided into salvation by an inner light.

Would Be Saved

In other words, Penn taught that Gentiles, such people as Socrates and others who had never had the advantages of Christianity, would be saved by this inner knowledge and understanding. To quote Mr. Wood: “William Penn’s estimate of the extent and spiritual value of Gentile enlightenment is more generous and less cautious than Amyraut’s. He writes in the spirit of Justin Martyr, of whom Rendel Harris says, “When he saw Socrates struggling in the sea, he was not content merely to throw him a rope to assist his salvation, but he hauled him on board the ship of Christian faith and bade him make himself at home with the crew.”

Like Justin Martyr, William Penn recognizes Christians before Christ. He was the more enthusiastic in his praise of Gentile divinity because in some particulars Greek philosophers supported Quaker testimonies. Socrates’ refusal to take fees for teaching and his condemnation of the Sophists for moneymaking was in line with Friends’ distrust of a paid ministry, and Penn was glad to find pre-Christian sages who condemned swearing and maintained Friends’ testimony against oaths. Penn pointed the contrast between these differences between Gentile divinity and the practice of professing Christians so sharply that he lent some color to Keith’s charge that he recognized only pagans as fellow Christians, and disowned all who profess and call themselves Christians other than Friends.”

This one paragraph, we believe, will suffice to show both Penn’s teaching on this subject and Wood’s apparently fair and unbiased criticism of it.

Political Beliefs

The chapter on William Penn, “Constitution Maker,” by Francis R. Taylor, is also of special interest to Americans and to all believers in democracy. And while Penn’s theory of government is perhaps better and more widely known than his theological doctrines, it is probable that few Americans entirely realize how much democracy owes to him.

As Mr. Taylor states: “Penn’s Holy Experiment, in spite of its faults, its weaknesses, its failures, and heartaches, was the working laboratory for the great political philosopher, whence he evolved his later theories that were to affect so profoundly the thought and action of Jefferson, the Adamses, Mason, Patterson, Franklin, and Wilson in the Constitutional Convention a century later.” The “great political philosopher” referred to is John Locke, who apparently had been greatly influenced by Penn.

But the Quakers, as such, have by no means been the only people to become influenced by this doctrine of “The Inner Light.”

Some years ago while we were teaching school in western Ohio, we frequently heard about that rather peculiar denomination or sect of people commonly called Mennonites. We refer to these people as rather peculiar because they differed so radically in many ways from the majority of people in the region in which they lived and in which many of them still live.

Not only did these people dress in a manner well calculated to attract attention in a crowd of others, but their beliefs sometimes brought them into conflict with their neighbors and occasionally with the law of the land. Yet oddly enough, we never heard a word of harm from any of them.

Regarded as Harmless

They were regarded as harmless, inoffensive, law-abiding, and worthy citizens, except on points where their religious doctrine conflicted with the law and on which points they chose to obey conscience rather than custom and bore hardships caused thereby with a fortitude worthy of great people struggling in a great cause.

As usual, perhaps, the public in general actually appears to know little about the real doctrines and practices of small groups like the Mennonites, except when and where those doctrines and practices cause a conflict with so-called public opinion.

We speak of the Mennonites as one of the small groups of people because, according to recent authoritative estimates, there are only about 75,000 of them in the United States, and these are divided into about 16 different subdivisions and branches. So in a land of 120,000,000 or more people, the few thousand belonging to any one branch of the Mennonites must form a comparatively small group. Of these, however, a considerable number are scattered throughout Ohio into which state they spread from Pennsylvania, where they first settled in 1683.

Because of their personal appearance, their doctrine of non-resistance, etc., the Mennonites are frequently confused with the Quakers, it appears. And there is a close relationship between these two sects both historically and theologically. Yet there are differences between them also. Therefore, since we have been recently discussing the Quaker migration to the Old Northwest Territory, this is perhaps a very appropriate time to consider the Mennonites as well.

Origin in Europe

First, let us consider their origin in Europe. The Mennonites, according to the best available data, were founded by Grebel, Manz, and Blaurock in Zurich in 1525, but for some reason or other they have become better known by the name of the leader in Holland, Menno Simons. The sect, which was never very large, apparently, became widely scattered throughout the central European nations, where they were subject to frequent and severe persecutions. It is difficult to see, from these bare facts, how the Mennonites can be so frequently confused with the Quakers, or if not exactly confused with them, at least considered as a branch of the same sect.

But when we compare the teachings of the two sects, it is easier to understand how those knowing little or nothing of their historical background might do just that. For we find that the bearing of arms in war, the taking of oaths, the granting of divorces, etc., are just as strongly condemned by the Mennonites as by the Quakers. We find, too, that they discourage the holding of political offices and in matters of faith are quite orthodox, professing belief in the usual evangelical teachings about God, the fall of man, repentance, baptism, etc.

Another reason the people of the United States apparently so frequently consider the Mennonites and the Quakers as one and the same sect historically as well as doctrinally is the fact that the first Mennonites to settle in this country were induced to do so by William Penn’s offer of religious freedom to settlers in his colony of Pennsylvania.

Spread Into Ohio

In response to that offer, a small band of Mennonites immigrated to Germantown, Pennsylvania, where they built one of their meeting houses.

From this small beginning, the Mennonites spread to other communities, then on westward to Ohio and later to Minnesota and Kansas. And from this one small band, which arrived in America in 1683, their number had increased by 1930 to something like 75,000, although as we have noted, they have also become divided into a number of branches.

From this small beginning, the Mennonites spread to other communities, then on westward to Ohio and later to Minnesota and Kansas. And from this one small band, which arrived in America in 1683, their number had increased by 1930 to something like 75,000, although as we have noted, they have also become divided into a number of branches.

But in spite of the similarity of the Mennonites and Quakers, and in spite of the common confusion of the two sects as one or branches of the same one, we are assured by students of the subject that such is not the case.

This can be seen by tracing and comparing the origin of the two sects: In Chapter VIII of “Children of Light,” William I. Hull discusses in some detail “The Mennonites and Quakers of Holland.” And although this title may have a sort of foreign sound to local readers, it contains much more valuable data than the mere title suggests.

Moreover, it should prove very enlightening to anyone who is confused about the relationship between the Mennonites and Quakers. After showing how Holland had become a refuge for persecuted religious sects long before Quakerism developed in England, Mr. Hull discusses the theory that the latter sprang from the Protestant Reformation. Of this he says:

Origin of Quakerism

“Some historians of Quakerism have sought to trace its origin back to the religious sects which sprang up in England during the course of the Protestant and Puritan revolutions in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth centuries. They have shown that indirectly and perhaps unconsciously the founders of Quakerism owed much to some of these sects, and especially to the Baptists.

One of them, William Tallack, a Quaker author of 1867, goes so far as to regard them as the direct ancestors of Quakerism. He declares: Both divisions of the Baptists, (the General and the Particular) had anticipated most of the doctrines and also the system of discipline, adopted by George Fox and the Friends. But it was the General Baptists (who were a distinct body as early as 1606), that had most fully arrived at the views and usages which have been subsequently attributed to Quaker origin.

The differences of opinion which arose amongst the Baptists (relative to election and reprobation) about the time of the Civil War resulted in many thousands joining the ranks of Fox and the Friends. Fox was rather the organizer or completing agent than the founder of Quakerism.”

However, the article continues to show that the best consensus on the subject is that while Quakerism and the Baptist movement had much in common, neither sprang from the other. Then taking up the relationship between the “Baptists and the Mennonites” and the “Mennonites and the Quakers,” the same conclusion is reached, it appears. This conclusion is that although the two sects agree on the essentials of doctrine, they are distinct and separate historically.

The Amish Sect

We have already noted how some of the Mennonites, in the early days of the settlement of whites in America, came to this country from Europe, in response to William Penn’s offer of freedom of worship in Pennsylvania. Among some of the early Mennonite settlers was a group of the so-called Aymish or Amish. This sect appears to be one of the numerous divisions of the Mennonites, and like the latter, takes its name from its founder Aymen. Some of these, or their descendants, later migrated westward, and several colonies or settlements of the Amish, as they appear to have been generally called in this region, settled throughout the Northwest.

One of the first Amish communities to attract attention in Ohio appears to have been one in Riley, Putnam County, in the extreme northwestern portion of the state. As this region was settled at a comparatively late date in the state’s history, these people must have been among the country’s first settlers.

A visitor to this community about 1845 refers to their peculiarities of appearance, etc., stating that they “wear long beards and reject all superfluities in dress, diet, and property,” but he appears anxious to emphasize also that: “They have ever been remarkable for industry, frugality, temperance, and simplicity,” and this appears to be about the general testimony regarding members of this sect by others who have known them.

Another interesting thing told of the Omish [sic] is at the time of their immigration to this country, they had neither churches nor graveyards.

Their Explanation

It is said that they explained this by saying, “A church we do not require, for in the depth of the thicket, in the forest, on the water, in the field and in the dwelling, God is always present.” Perhaps somewhat of the same reasoning accounted for their lack of cemeteries. Certainly, there was abundant space for them to lay away the remains of their dead while the maintenance of regular burial grounds would probably have appeared as a sort of worldly vanity to them.

Of course, later some of this sect departed from their more primitive ways, but it has always remained enough different from others and from society in common to be generally called “strange.” We refer here especially to the Omish [sic], although the same description fits the Mennonites in general.

A very valuable contribution to the history of the Friends is contained in Chapter III of “Children of Light.” This chapter is a contribution by Dr. Harlow Lindley on “The Quaker Contribution to The Old Northwest” and should prove of great interest to our readers who have been interested in our recent discussion of this subject in these columns.

Dr. Lindley, as you may know, is an official of the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society and is well qualified to speak on the subject. You may recall that we showed how, apparently, the first real settlement of Quakers in the Northwest and in what is now Ohio, was made at Quaker Bottom, now Proctorville, during the closing years of the 19th Century, but that Thomas Beals had been on the ground as a missionary and explorer much earlier, probably about the time the Declaration of Independence was signed.

No Real Contradiction

There is no real contradiction to this in the following quotation from Dr. Lindley, although he does not mention Quaker Bottom:

“The first direct contact of Friends with The Old Northwest, so far as we have positive proof, was in 1773, just 10 years after Great Britain had secured title to the territory from France. Two Friends, members attending the Philadelphia yearly meeting, Zebulon Heston and John Parrish, prompted by a desire to make a religious visit to the Delaware Indians who had moved westward into the eastern part of what is now the state of Ohio, spent about 10 weeks making a trip in order to express their interest in the welfare of these first Americans.”

Moreover, Dr. Lindley continues: “The first Friends’ minister to cross the Ohio River and preach within the limits of The Northwest Territory was Thomas Beals …, etc.,” and in another place, he says: “In the year 1796, George Harlan and family, members of the Society of Friends, moved to the Ohio region. So far as known, this was the first Quaker family to locate in The Northwest Territory.

In February 1797, Jesse Baldwin and Phineas Hunt crossed the Ohio River. Now you may recall that Jesse Baldwin, according to the old Quaker manuscript and other evidence to which we recently referred, was one of the leaders in the settlement at Quaker Bottom, now Proctorville, in 1797 or 1798. Thus, we have this added evidence of the priority of this settlement among the Quaker settlements in what is now Ohio.

Quaker Beliefs

In his discussion of “Quakers of The Old Northwest,” Dr. Lindley explains the Quaker attitude on important questions of the various periods of history in which they have figured, such as their relations with the Indians, with slavery, their attitude toward education, politics, etc. We have already seen how they, better than any other group of people, were able to get along with the Indians and how concerned they were over the salvation of the natives.

Those familiar with the anti-slavery controversy know, too, how staunch the Quakers were in opposition to slavery. Despite their doctrine of non-resistance, they found many ways of assisting fugitives and hindering the pursuit of slave hunters. Dr. Lindley, however, brings out one point which many have apparently overlooked, and that is the hardship this brought upon the Quakers of the south.

Says he: “The exodus of Friends from the South, on account of slavery, presents one of the most pathetic scenes in American history. The number of those who migrated amounted to thousands. Almost all left George and South Carolina, and Virginia was so weakened that the Virginia yearly meeting was laid down after it had existed for almost a century and a half.”

This is a fact that few people appear to have considered, and the same may be said of the result, which Dr. Lindley describes thus:

“While the South lost some of its best citizens by the removal, those that came north to Ohio and Indiana had much to do in making them the strong, liberty-loving states they became.”

Opposition to Slavery

In Indiana, a determined effort was made to introduce slavery into the Territory; and the Friends, by their persistent efforts, working through “Log Conventions” and in every other possible way, furnished much of the agitation that succeeded in defeating the pro-slavery sentiments. Theodore Clark Smith says, “Wherever the Quakers settled, we can trace the anti-slavery agitation.”

Dr. Lindley also shows how the Quakers were among the first settlers of Ohio to recognize the need of elementary, secondary, and higher education in The Old Northwest Territory. Such sections as Columbiana County, where they settled in comparatively large numbers, became “fairly dotted with Friends’ schools,” while their early schools in Indiana set the standard for the public school system later founded there.

But it is in their relation to politics and statesmanship that the Quakers have left a record which may appear strange, if not surprising, to many, in view of the generally accepted belief that Quakers refuse to participate in such affairs. It is true that the Quakers have generally held aloof from politics in the ordinary, accepted meaning of the term, especially certain branches of their sect and certain related sections, such as the Mennonites, Omish, etc.

But many had no apparent hesitation in taking the lead in matters of public interest when great moral questions were at stake. As Dr. Lindley points out, a great number of prominent statesmen of the country, particularly of Ohio and Indiana, have been either Quakers or descendants of Quakers.

Stanton Was Quaker

For instance, few students of the life of Edwin M. Stanton, the celebrated secretary of war, would perhaps think of him as a very devout Quaker. Yet one of his grandmothers was among the first group of Quakers to settle in eastern Ohio. Joseph O. Cannon, better known as “Uncle Joe” Cannon was another statesman whose appearance and actions were not always remindful of the doctrine of Friends, and yet his father was one of the leading Quakers in Indiana and later of Illinois.

Perhaps the greatest example similar to present-day citizens of the Quaker statements is former President Herbert Hoover, who is said to be descended from a family of Quakers that was once, for a time, established in Ohio.

Dr. Lindley points out, too, that it has been claimed with much reason that the defeat of Henry Clay for the presidency may have been due to an affair that occurred at Richmond, Indiana, in 1942, when he failed to satisfy some Quakers who asked him some questions during a speech there. In answering those questions, Mr. C. took a position unpopular in the north and south alike.

In business, the Quakers, Mennonites, Omish, and apparently related sects have been almost universally noted for their thrift and industriousness. They have chiefly engaged in stock raising, fruit raising, and gardening.

And so it is easy to see that the Quakers, as well as their related sections, the Mennonites and others, have made a real contribution to the industrial, social and educational, as well as the religious life of The Old Northwest as well as practically every other region in which they have dwelt.

Well, perhaps the reader has come to the conclusion by this time that this is a rather rambling sketch. However, as we hope we made clear at its beginning, we have aimed to merely make plain in general terms just who the Quakers of The Old Northwest really were and just what they represented both religiously and otherwise while discussing their closely related brethren, the Mennonites, basing our conclusions on controversial matters upon the authority of the volume entitled “Children of Light.” Of course, if you wish a far more detailed discussion of the subject from almost every angle apparently, we believe you should read that work itself.

We have stressed the Mennonites in our sketch because we had not before discussed them in these columns. Moreover, what references we have made to the Quakers themselves in this article merely supplement what we had already written about them.

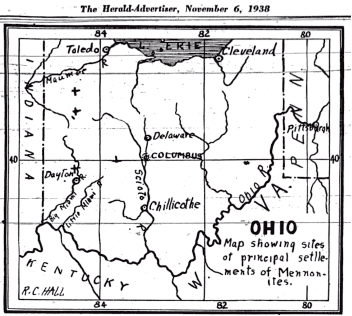

It may be interesting to learn that whereas the Quakers themselves settled largely in the southeastern part of Ohio, the Mennonites settled chiefly in the Northwestern part of the state. This refers, of course, to their early settlements to which they may have moved subsequently. However, in many instances, their descendants remain to this day in the very same vicinities in which the original settlers located a century or more ago. Thus Allen and Putnam’s counties remain the principal Mennonite communities in Ohio to this day.

Thanks Debbie I appreciate it!

Martha

I discovered a Quaker journal in the WVU archives. I ordered a copy a few months ago. I will read it again to see if any of the names match this area.