An Underground Railroad Conductor Interviewed

Ironton Register, October 31, 1878

James Ditcher is a modest mulatto, gently gliding into the twilight of 50 years of age. He came to Ironton, Ohio, over 25 years ago, and in that time has passed through many romantic experiences and always comes up smiling. It is hardly supposable. With all his hard knocks and hair-breadth escapes, he was ever submerged in the billows of anguish. Many times, when the tide of the world seemed to be running against him, James’s philosophical soul would break out in titillating wrinkles all over his face.

The other day, James was standing on the corner of Third and Railroad, leaning on a pile of tile, when a Register reporter interviewed him.

Notwithstanding, only recently, one had shot at his wife as she stood in the door of her domicile. Not a cloud of sorrow dwelt on his brow. The bright sun was warming, and James never wore a more friendly smile.

Years ago, and before the war, James Ditcher was responsible. It was not a paying office and not by any means a safe one. He made no parade of it. On the other hand, he kept it a profound secret. Sometimes, people would allude to his important official relations, but James’s innocent smile would throw them off track.

James was often observed in the execution of his official duties, but he would conjure up a fascinating smile and tell an infantile tale, and oblivion would ensue. Yes, James was a conductor on the Underground Railroad, and on many a train, he has run toward the North Star.

And this was the “subject of the story” which Mr. Ditcher modestly unfolded to the Reporter. James is not as quiet as he was 20 years ago. He grows somewhat thrilling and discursive when now he relates his personal experiences. Thinking some things he said would be interesting to print, the Reporter jotted down in substance James’s narration:

“From 1855 to 1860,” says he, “I was largely connected with the underground railway. I must have taken through nearly 300 slaves in that time. The route we’d take was to Olive Furnace, or Squire Stewart’s in Symmes Township, then to Noah Nooks at Berlin crossroads, and from there to Wilkesville, in Vinton County. I would take them from Ironton to Olive or Symmes, and then another fellow would take them to the next station.”

“Of course, I never did this for money and never got a cent except for a free slave trying to get away with his wife and girl. He was the scariest fellow, and a perfect baby, too. Near Olive, while I was trying to get through the woods into Symmes, the free slave said he must have something to eat. I told him he mustn’t show himself to anyone, or we would surely be gone up. But he said he wouldn’t starve, and he went into a coaling job down the hill.

I knew we were pursued and thought that would let the cat out of the bag. So the women and I went on to a high point, where I climbed a maple tree to see if I could see the free slave, and sure enough, down in the coating, I saw him and a lot of men around him. Soon the man jumped, and away he scampered, the men after him. I had told him before what direction to take, so I waited for him.

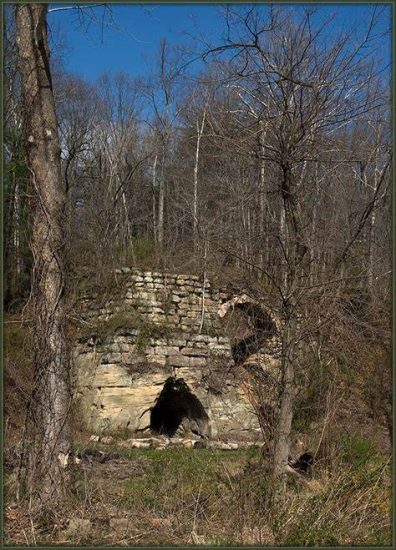

Photo of Olive Furnace from the Lawrence Register Archives

Soon he came tearing through the woods, puffing and blowing, and we slipped off the hilltop down the hillside and among the thicket. While creeping quietly through that, some man just above us yelled. The free slave jumped as if he was snake bit. Both women had carpet bags, and I took and told the women to follow down the hill.

I could hear the slave catchers on our tracks. Just then, we came to a big tree that had fallen and lay down the hill. Under this, I scrounged the women and their carpet sacks and told them I lit out when dark came to go down into the hollow and travel in this direction (pointing toward Symmes). They did as they were told, and the next morning they and the man were over on Symmes Creek, safe. They got through all right, but I never saw them since.

“Another time, a gang of five came over – a man, his wife, and three children. I then kept a saloon on Lawrence St. I took the three children and shut them up in the garret over the saloon. Several fellows came that day looking for the runaways, but I told them I hadn’t seen any. The old man and woman were hiding in a house on Sixth Street near Buckhorn.

The slave catchers, assisted by an officer, surrounded the house, and things looked pretty blue for the runaway slaves. I had about given up, but when the officer went away to see about a warrant, we slipped the runaways out, and by the time the slave catchers moved up to bag their game, we had them hidden safely in the house of a rich lady of this town.

“Who is the rich lady?” asked the Reporter. “Oh, I won’t tell that,” said James, “she’s a mighty good woman and was mighty glad to hide the slaves, and they stayed there until night when they and the children were put in charge of a barber then living here. He took them as far as the ‘beech woods’ two miles below town but, getting scared, abandoned them, leaving them in the woods.

I went down then and helped them on. They went through the woods all the time, passed in sight of Buckhorn Furnace, and got safely out of this county and were not retaken. On returning to town, I met three or four slave catchers looking for the trail. Before I knew it, I was right on them and had to walk between them. La, but I was scared just then. They looked wicked at me.

“I remember once, a small gang of three came down here – one of them was a woman with a baby. They were brought down in a skiff by some other free slaves. The slave catchers were close onto them when they got here. My, but they threshed and ducked the men that rowed that skiff! Things had to be done in a hurry, and to get away with that woman and baby, too, was a big thing.

I went to John Campbell’s stable and sneaked out a horse. Preacher Chester loaned me his horse and side saddle. We started and pushed as fast as we could. Late at night, we got to Mr. Harris’s, a colored man living near Olive Furnace. There we stayed until morning. The pursuers were close on us; they stopped for the night two miles this side of us at a whiskey shop but got tight and the next morning didn’t get on the chase until we were several miles ahead.

“We got safe to the Stewart settlement, and then a young fellow took charge of the gang and helped them to Nooks at Berlin crossroads. On my way back, I met the fellows who were after the slaves. I knew them – one was Mose Claybaugh, another Captain ____, and the third was the owner of the slaves.

“I was riding Mr. Campbell’s horse and leading Preacher Chester’s with the side saddle on. They asked me what I had been doing with that horse and side saddle. I told them I had been to Gallipolis to a dance and had had my girl with me. They called me a d__n liar, threatened to shoot me, and swore they would shave Chester’s horse’s tail. I sided away from them, and they did not disturb me.”

James told the Reporter several other incidents, narrating them as if they were occurrences of the past week. During his recitals, he would speak of the assistance and advice of certain men, but when asked who those men were, he shook his head and smiled.

Ditcher was a very successful conductor. He never lost but two or three slaves, and they were captured after they left him once near where lower’s store. He parted with two slaves directing them to Bloom Switch, where they could take the cars. They got through all right, but when in the car, they were nabbed and taken back to Kentucky.

But to prevent capture, the utmost secrecy and privation were required. They would always have to travel by night or slip through the woods and along the ridges, avoiding the residences, diggings, or coal jobs. A gang would hardly ever start out, but the news of their escape preceded them; and all strange slaves on the line were at once suspected and captured, as the rewards were generally lucrative.

It made no difference what James was doing; he would drop everything when train time came. He is a plasterer by trade and often has thrown down his tools and left a ceiling half-covered with mud or skim to assume his more important duties of conductor of the “underground.” You wouldn’t think it to look at him, that he was a dashing liberator, but he never shunned a post of danger. His trains departed and arrived while the people slept securely at their homes.

Business on the “underground” has ceased, but James is as youthful and smiling as ever.

0 Comments